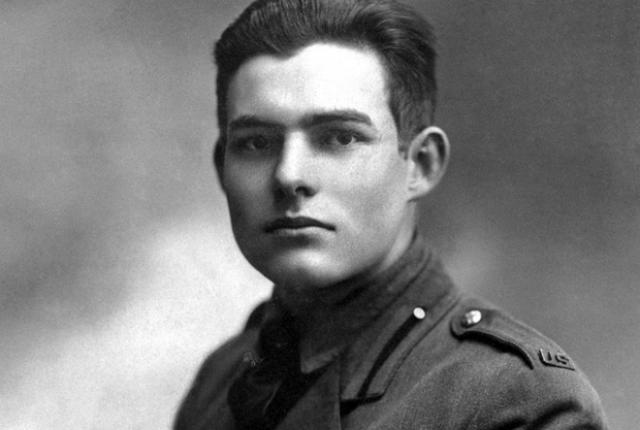

Before Ernest Hemingway was a literary giant, he was a cub reporter. When Hem graduated high school at 18, he moved to Kansas City and started a six-month stint with the Kansas City Star—a job that molded his trademark punchy, staccato style.

Some of his early reporting feels rushed and raw. The pieces read like the typical journalese you see today (except that it rattled off lots more statistics about army recruiting events). But the longer Hemingway stayed at the Star, the more his style matured—and the more literary it became. Here are snippets from three of his articles.

1. “AT THE END OF THE AMBULANCE RUN” (JANUARY 20, 1918)

Hemingway was so driven to get a story, it’s said that he would chase ambulances down the street. After working at the Star for three months, he finally got the nod to write about a hospital nightshift. In it, Hemingway abandoned the stiff reportorial tone demanded by his editors and, instead, opened the piece as if it were a short story:

The night ambulance attendants shuffled down the long, dark corridors at the General Hospital with an inert burden on the stretcher. They turned in at the receiving ward and lifted the unconscious man to the operating table. His hands were calloused and he was unkempt and ragged, a victim of a street brawl near the city market. No one knew who he was, but a receipt, bearing the name of George Anderson, for $10 paid on a home out in a little Nebraska town served to identify him.

The surgeon opened the swollen eyelids. The eyes were turned to the left. “A fracture on the left side of the skull,” he said to the attendants who stood about the table. “Well, George, you’re not going to finish paying for that home of yours.”

“George”’ merely lifted a hand as though groping for something. Attendants hurriedly caught hold of him to keep him from rolling from the table. But he scratched his face in a tired, resigned way that seemed almost ridiculous, and placed his hand again at his side. Four hours later he died.

Where other reporters would have treated flesh-and-blood people as mere names on paper, Hemingway made them into characters. In “Ambulance,” he experimented with dialogue to create both a plot and a back-story. According to Dr. R. Andrew Wilson, this is where Papa Hem honed his own brand of subtle, heartstring-tugging irony. Like this:

One day an aged printer, his hand swollen from blood poisoning, came in. Lead from the type metal had entered a small scratch. The surgeon told him they would have to amputate his left thumb.

“Why, doc? You don’t mean it do you? Why, that’d be worsen sawing the periscope off of a submarine! I’ve just gotta have that thumb. I’m an old-time swift. I could set my six galleys a day in my time — that was before the linotypes came in. Even now, they need my business, for some of the finest work is done by hand.

“And you go and take that finger away from me and — well, it’d mighty interesting to know how I’d ever hold a `stick’ in my hand again. Why, doc!–”

With face drawn, and head bowed, he limped out the doorway. The French artist who vowed to commit suicide if he lost his right hand in battle, might have understood the struggle the old man had alone in the darkness. Later that night the printer returned. He was very drunk.

“Just take the damn works, doc, take the whole damn works,” he wept.

2. “SIX MEN BECOME TANKERS” (APRIL 17, 1918)

As the war across the pond roiled, Hemingway was asked to cover the national tank training camp in Gettysburg, Pa. Instead, he came back with a piece about what it’s like to be inside a tank during an attack.

The machine gunners, artillerymen and engineers get into their cramped quarters, the commander crawls into his seat, the engines clatter and pound and the great steel monster clanks lumberingly forward. The commander is the brains and the eyes of the tank. He sits crouched close under the fore turret and has a view of the jumbled terrain of the battle field through a narrow slit. The engineer is the heart of the machine, for he changes the tank from a mere protection into a living, moving fighter.

The constant noise is the big thing in a tank attack. The Germans have no difficulty seeing the big machine as it wallows forward over the mud and a constant stream of machine gun bullets plays on the armour, seeking any crevice. The machine gun bullets do no harm except to cut the camouflage paint from the sides.

The tank lurches forward, climbs up, and then slides gently down like an otter on an ice slide. The guns are roaring inside and the machine guns making a steady typewriter clatter. Inside the tank the atmosphere becomes intolerable for want of fresh air and reeks with the smell of burnt oil, gas fumes, engine exhaust and gunpowder.

The crew inside work the guns while the constant clatter of bullets on the armour sounds like rain on a tin roof. Shells are bursting close to the tank, and a direct hit rocks the monster. But the tank hesitates only a moment and lumbers on. Barb wire is crunched, trenches crossed and machine gun parapets smothered into the mud.

Then a whistle blows, the rear door of the tank is opened and the men, covered with grease, their faces black with the smoke of the guns, crowd out of the narrow opening to cheer as the brown waves of the infantry sweep past. Then it’s back to barracks and rest.

3. “MIX WAR, ART, AND DANCING” (APRIL 21, 1918)

This was Hemingway’s final—and favorite—Star article. By this point, he had abandoned the typical “who, what, where, when” journalistic lede and started the article with a scene and character instead.

Outside a woman walked along the wet street-lamp lit sidewalk through the sleet and snow.

The story was supposed to be about a soldiers’ dance with ladies from a fine arts institute. But instead, Hemingway focused on comparing the happy couples frolicking inside with a lonely streetwalker outside. (Although he never says it explicitly, the woman is a prostitute. Hemingway slyly applied his “iceberg theory” to journalism here.)

Three men from Funston were wandering arm in arm along the wall looking at the exhibition of paintings by Kansas City artists. The piano player stopped. The dancers clapped and cheered and he swung into “The Long, Long Trail Awinding.” An infantry corporal, dancing with a swift moving girl in a red dress, bent his head close to hers and confided something about a girl in Chautauqua, Kas. In the corridor a group of girls surrounded a tow-headed young artilleryman and applauded his imitation of his pal Bill challenging the colonel, who had forgotten the password. The music stopped again and the solemn pianist rose from his stool and walked out into the hall for a drink.

A crowd of men rushed up to the girl in the red dress to plead for the next dance. Outside the woman walked along the wet lamp lit sidewalk.

In his Cambridge Companion to Hemingway, Scott Donaldson writes that “Hemingway’s references to the prostitute at the beginning, middle, and end of the article show that he is learning to use the fictional technique of framing even in journalism. They demonstrate his tendencies to avoid convention, to reach toward methods that reveal more about the natures of people than facts alone can, and to communicate the significance of events through internal, rather than or in addition to external, reference, all of which will recur in his fiction.” You can see that as he wraps up the story:

The pianist took his seat again and the soldiers made a dash for partners. In the intermission the soldiers drank to the girls in fruit punch. The girl in red, surrounded by a crowd of men in olive drab, seated herself at the piano, the men and the girls gathered around and sang until midnight. The elevator had stopped running and so the jolly crowd bunched down the six flights of stairs and rushed waiting motor cars. After the last car had gone, the woman walked along the wet sidewalk through the sleet and looked up at the dark windows of the sixth floor.

via:mentalfloss.com