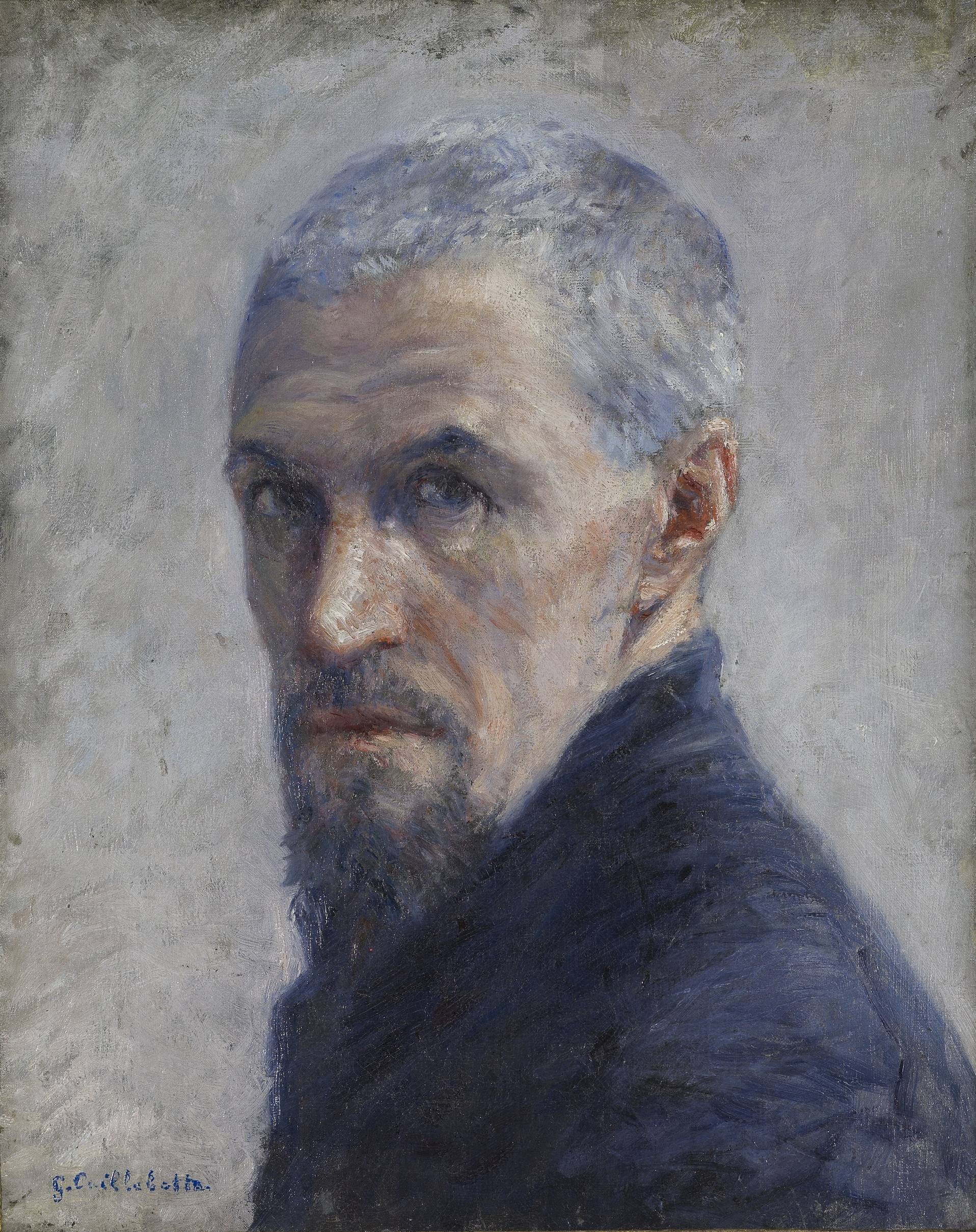

A Name You Should Know, But Probably Don’t

Every art lover has heard of Monet, Renoir, and Degas. Their works are plastered across museum walls, tote bags, and overpriced coffee table books. But what about Gustave Caillebotte? The man who not only painted with razor-sharp precision but also funded the entire Impressionist movement? Ah, yes. The forgotten genius—the “less famous” Impressionist who made everyone else’s success possible.

Gustave Caillebotte was born rich, painted masterfully, and yet, for most of history, he was a footnote in the grand Impressionist saga. Why? Because he didn’t die poor and miserable, of course. The art world has a peculiar affection for the tortured, struggling artist—an identity Caillebotte never fit. Instead, he painted what he pleased, bought what he liked, and left behind a legacy that took over a century to be recognized.

Caillebotte’s Place in the Impressionist Pantheon

Unlike his contemporaries, Caillebotte didn’t have to struggle against financial constraints, critics, or public indifference. He had the luxury of painting whatever he wanted without worrying about whether it would sell. This, ironically, made him an outlier in the Impressionist movement, even though he was one of its most crucial figures. He was both artist and benefactor, a unique hybrid that history has had trouble categorizing.

Despite his wealth, Caillebotte was no dilettante. His paintings showcase an unparalleled mastery of perspective, light, and urban realism. He captured a Paris that was changing rapidly under Baron Haussmann’s renovations, offering a visual record of the shifting dynamics of modernity. Unlike Monet’s romanticized gardens or Renoir’s dreamy picnics, Caillebotte’s work had an edge—an almost photographic clarity that set him apart.

The Forgotten Patron of Impressionism

If Caillebotte had been just another painter, he might have been remembered more fondly. But the problem was that he was also the man who kept Impressionism afloat financially. He bought works by Monet, Renoir, Pissarro, and Degas at a time when no one else wanted them. He paid for exhibitions, supported struggling artists, and even helped his friends pay rent. His collection, when later bequeathed to the French government, helped define Impressionism as the major artistic movement it is known as today.

But as with so many patrons of the arts, history has a habit of celebrating the artists while conveniently forgetting the financiers. Caillebotte’s paintings weren’t displayed prominently in major museums for much of the 20th century, and his contributions as a patron were downplayed. Unlike the Medici family, whose patronage is celebrated, Caillebotte was treated as a secondary character in the movement he helped create.

Why Didn’t Caillebotte Fit the Impressionist Mold?

One reason Caillebotte didn’t gain immediate recognition is that his style was different. While his paintings were Impressionist in spirit, they were often more realistic than the soft, blurry strokes of Monet and Renoir. His work had a sharpness to it that was almost photographic, and his compositions were highly structured.

Consider Paris Street; Rainy Day (1877). The crispness of the architecture, the symmetry of the umbrellas, and the almost mathematical perspective make it feel more like a precursor to modern photography than a traditional Impressionist painting. This wasn’t a scene of fleeting light effects but a carefully composed vision of urban life.

Art critics and historians, accustomed to defining Impressionism by its looseness and spontaneity, weren’t sure what to make of Caillebotte. Was he an Impressionist? A Realist? A bridge between the two? The uncertainty surrounding his classification contributed to his marginalization in art history.

A Legacy Rediscovered

It took nearly a century for Caillebotte to be fully recognized for his contributions. In the late 20th century, museums and scholars began to reevaluate his work, and his role as both an artist and benefactor of Impressionism was acknowledged. His paintings, once overlooked, are now celebrated for their unique perspective on modernity. Paris Street; Rainy Day is now one of the most recognizable works of 19th-century art, and his collection of Impressionist paintings helped define the movement.

Today, Caillebotte’s name is no longer a mere footnote, but there is still work to be done in cementing his legacy. He may not have suffered for his art, but his contributions—both as a painter and a patron—were invaluable. It’s time to give him the recognition he deserves.

This article will explore Caillebotte’s work, his unique status as an independently wealthy artist, his role in shaping Impressionism, and, of course, the sheer absurdity of his historical underappreciation.

Balconies, Windows, and the Art of Looking

If there’s one theme Caillebotte mastered, it was the art of looking. Not just painting, but truly seeing the modern world. His works featuring balconies and windows aren’t just pretty snapshots of urban life—they are existential studies in voyeurism, separation, and longing. Through these compositions, Caillebotte captured not just the physical act of observation but the emotional and psychological weight that comes with it.

The Act of Looking as a Theme

Unlike many of his Impressionist peers, who focused on the transient effects of light and color, Caillebotte was intensely preoccupied with composition, structure, and perspective. His balcony and window paintings are not just visual records of Parisian life; they are meditations on perception itself. His figures are often positioned with their backs to the viewer, engaged in quiet contemplation, mirroring our own role as observers of his work. The viewer, then, becomes complicit in the act of looking, reinforcing the themes of detachment and introspection that run through these pieces.

Young Man at His Window (1875): A Study in Distance

Take Young Man at His Window (1875), for example. A well-dressed figure stands at an open window, gazing out at Haussmann’s redesigned Paris. We see his back, but not his face. This is a man seemingly poised between two worlds—the intimate interior and the expansive, ever-changing city beyond.

What is he thinking? Is he admiring the view, contemplating his place in modern society, or yearning for something beyond his luxurious existence? Caillebotte, always the astute observer, leaves it up to us. By turning his figure away from the viewer, he invites speculation. This is not merely a portrait but a psychological study, a moment frozen in time that captures the loneliness and introspection often hidden beneath the sheen of wealth and modernity. The open window acts as both an invitation and a barrier, symbolizing the thin line between engagement and detachment in urban life.

View from a Balcony (1880): The Dividing Line

Then there’s View from a Balcony (1880), where the iron railing divides the composition, subtly reinforcing themes of isolation and modern detachment. Unlike his fellow Impressionists, who favored dappled light and spontaneous movement, Caillebotte’s compositions were carefully structured, often more akin to photography than traditional painting.

The view itself is striking—a carefully measured arrangement of architecture, greenery, and sky—but it is the placement of the railing that transforms the scene. The balcony serves as a literal and metaphorical threshold. We, as viewers, are kept at a distance, much like the figure standing behind the railing. The city is right there, full of promise and movement, yet something keeps us (and the subject) from fully engaging with it. The placement of the railing suggests a quiet alienation, a reflection of the impersonal nature of urban life.

Man on a Balcony, Boulevard Haussmann (1880): The Urban Observer

But let’s not forget the eeriest of them all—Man on a Balcony, Boulevard Haussmann (1880). Here, the city sprawls out below, yet the figure remains distanced, disconnected. Dressed in a formal black suit, he stands stiffly at the edge, observing but not engaging. The city hums with life, but he remains detached, a silent spectator to the bustling world below.

It’s as if Caillebotte is preemptively capturing the alienation of the modern urbanite—a sentiment we usually credit to Edward Hopper or German Expressionists decades later. This painting feels startlingly contemporary, evoking the same sense of existential solitude found in 20th-century cinema and literature. In today’s world of skyscrapers, smartphones, and digital detachment, this image of a man staring blankly at an indifferent metropolis resonates more than ever.

Windows as Frames: A Cinematic Approach to Painting

What makes Caillebotte’s window and balcony paintings so effective is his ability to use framing devices in a way that feels almost cinematic. The window or balcony becomes a lens, a controlled way of viewing the world beyond. This technique mirrors the experience of looking through a camera or watching a scene unfold on a screen. By doing so, Caillebotte not only anticipates later developments in photography and film but also deepens the psychological impact of his paintings.

The use of sharp angles, strong verticals, and carefully measured distances creates a sense of depth and perspective that draws the viewer into the scene. But rather than immersing us in the action, these compositions hold us at arm’s length. We are observers of observers, caught in a recursive loop of looking without ever truly participating.

Comparisons to Vermeer and Hopper

This recurring theme places Caillebotte in the lineage of great painters of solitude, from Vermeer to Hopper. Like Vermeer, he constructs meticulously arranged interior spaces that hint at inner lives beyond what is depicted. Vermeer’s Woman in Blue Reading a Letter (1663-64) and Caillebotte’s Young Man at His Window share a similar sense of quiet anticipation, of lives in limbo.

Similarly, his ability to capture modern urban isolation aligns him with Hopper, whose paintings of solitary figures in diners, apartments, and hotel rooms defined American realism in the 20th century. Man on a Balcony, Boulevard Haussmann could easily be the Parisian predecessor to Hopper’s Nighthawks—a stark exploration of loneliness in the midst of a thriving city.

The Psychological and Social Barriers of 19th-Century Paris

The window and balcony motif isn’t just an aesthetic choice; it’s a powerful metaphor for the psychological and social barriers of 19th-century Parisian life. Caillebotte was painting at a time when Haussmann’s renovations had radically transformed Paris. Wide boulevards replaced narrow, medieval streets, and grand new buildings redefined the city’s skyline. The modern metropolis was built for spectacle, designed to be seen and admired. Yet, Caillebotte’s figures, rather than reveling in this grand design, seem trapped within it.

His paintings suggest that modernity, for all its advancements, also brought with it a new form of disconnection. The city is beautiful, yes, but it is also impersonal, a place where people can exist side by side without ever truly interacting. The figures in his balcony and window paintings embody this paradox—they are present but removed, part of the city but separate from it.

Relevance in the Digital Age

In today’s hyper-connected yet emotionally detached world, Caillebotte’s balcony and window paintings feel eerily prescient. Social media, smartphones, and digital screens have become our new windows and balconies, allowing us to observe the world from a safe distance. We scroll through endless feeds, watching but not engaging, much like the figures in Caillebotte’s paintings.

His work reminds us that the act of looking is not always passive—it shapes our perception of the world and our place within it. Are we participants in life, or merely spectators? Are we admiring the cityscape, or yearning for something more? Caillebotte doesn’t give us the answers, but he forces us to ask the questions.

A Painter for Our Time

Ultimately, Caillebotte’s fascination with windows and balconies transcends his era. His paintings are not just studies of 19th-century Paris but timeless meditations on human perception, modernity, and isolation. As we continue to navigate an increasingly digital and disconnected world, his work remains as relevant as ever. His figures stand at their windows, looking out—but in many ways, they are looking at us.

Underappreciated, Underrated, and Unfairly Ignored

The Artistic Identity Crisis: Too Real for Impressionism, Too Modern for Realism

Gustave Caillebotte’s work exists in a liminal space between Impressionism and Realism, a fact that has contributed significantly to his historical neglect. While his contemporaries such as Monet and Renoir embraced the soft, feathery brushstrokes and atmospheric light effects that defined Impressionism, Caillebotte maintained a sharp, almost photographic precision in his compositions. His paintings, such as Paris Street; Rainy Day (1877), do not dissolve into light and movement in the same way Monet’s Impression, Sunrise (1872) does. Instead, they feel composed, calculated, and strangely modern.

Caillebotte’s approach to painting differed from the Impressionist ideal in both technique and execution. While Impressionists emphasized spontaneity and capturing ephemeral moments, Caillebotte used linear perspective, geometric precision, and structured compositions that made his works feel almost architectural. His perspective work was so advanced that some art historians have argued his paintings anticipated photographic compositions decades before they became a staple in modern photography.

Yet, despite this technical prowess, his work was often seen as too rigid, too precise, and even too polished to be fully embraced as Impressionist. On the other hand, his themes—urban life, modernity, fleeting moments—were far removed from the traditional academic subjects of Realism. This left Caillebotte in an artistic purgatory, one that did not allow him to be fully embraced by any movement, which in turn contributed to his marginalization in art history.

The Role of Wealth in Artistic Recognition

The trope of the “starving artist” has long been a fixture in art history, shaping public and critical perception of what makes an artist “authentic.” Figures like Van Gogh, who suffered poverty and madness, or Monet, who faced financial struggles before achieving success, fit neatly into this narrative. Caillebotte, however, was an outlier—he was born into wealth, never had to sell paintings to survive, and was more often recognized as a patron of Impressionism rather than a participant.

Because Caillebotte had the financial means to support himself, he did not need to conform to market demands or tailor his work for commercial appeal. This freedom, while beneficial artistically, had significant drawbacks in terms of visibility. His paintings were not widely circulated in galleries or salons during his lifetime, nor were they aggressively marketed posthumously by struggling heirs or dealers, as was the case with many other artists. As a result, his work did not enter the collective consciousness in the same way that those of Monet, Renoir, or Degas did.

Additionally, there is an inherent bias in art history that favors struggle and suffering. The idea that great art must be born of hardship meant that Caillebotte’s contributions were often downplayed. His wealth made critics reluctant to take him seriously, as if his financial privilege diminished his artistic credibility. This perception was both unfair and historically damaging, as it led to his exclusion from many key discussions about the development of modern art.

Limited Circulation and Institutional Neglect

Another reason for Caillebotte’s historical obscurity lies in the limited exposure of his work. While artists like Monet and Degas were actively exhibiting their paintings, seeking recognition, and networking with collectors, Caillebotte had the luxury of painting purely for personal satisfaction. Many of his works remained in private collections, unavailable to the public eye for decades after his death.

Additionally, because Caillebotte’s heirs did not engage in aggressive posthumous promotion, his works did not gain the same institutional recognition that other Impressionists enjoyed. Museums and galleries played a critical role in shaping the Impressionist canon, and without active champions to push his work forward, Caillebotte remained a footnote rather than a central figure.

It wasn’t until the late 20th century that major institutions began to reassess his contributions. The Gustave Caillebotte: The Painter’s Eye exhibition in 2015 at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. was one of the first major retrospectives to position him as a leading Impressionist rather than a mere patron of the movement. This renewed interest has helped elevate his status, but for nearly a century, institutional neglect had kept him in relative obscurity.

The Biases of Art History and the Power of Narrative

Art history is not a neutral field; it is shaped by the narratives constructed around artists and their works. Some artists are mythologized, their struggles and triumphs romanticized, while others—like Caillebotte—are left in the margins, their contributions minimized by the dominant discourse.

Caillebotte’s lack of a compelling personal tragedy made him less appealing as a historical figure. He was not a tortured genius, nor did he die penniless and unrecognized. Instead, he lived comfortably, painted what he wanted, and supported his peers. This lack of drama contributed to his exclusion from the grand narrative of Impressionism.

Furthermore, the Impressionist movement itself became synonymous with the more traditionally recognized figures—Monet, Renoir, Degas, and Manet. Once an artist’s place in history is established, it becomes difficult to revise. Because Caillebotte’s role was not clearly defined during his lifetime, his name was simply omitted from many early accounts of Impressionism. The result was a self-perpetuating cycle of neglect, where his absence from major art history texts led to continued obscurity.

The Ironic Fate of an Impressionist Champion

Perhaps the greatest irony of Caillebotte’s legacy is that his dedication to Impressionism may have contributed to his own erasure. While he worked tirelessly to support his fellow artists—purchasing their paintings, funding their exhibitions, and even advocating for their recognition—his own work remained secondary in the eyes of history.

Caillebotte’s greatest contribution to Impressionism may not have been his paintings, but his role as a benefactor. His purchases provided financial stability to Monet, Renoir, and others, allowing them to continue their work. However, because he was seen primarily as a patron rather than an artist, his own paintings were overshadowed by the movement he helped sustain.

It is only in recent decades that Caillebotte’s contributions as a painter have been reevaluated. His unique perspective, technical mastery, and forward-thinking compositions are now receiving the attention they deserve. However, the damage of a century of neglect remains, and he is still often viewed as a secondary figure in Impressionist history rather than one of its central innovators.

Reclaiming Caillebotte’s Place in Art History

Caillebotte’s artistic legacy is one of brilliance overshadowed by circumstance. His technical precision, modern perspectives, and bold compositions were ahead of their time, yet his wealth, limited circulation, and lack of personal struggle contributed to his historical neglect. As art history continues to evolve, there is hope that his name will finally take its rightful place alongside the giants of Impressionism.

The reassessment of Caillebotte’s work serves as a reminder that art history is not fixed—it is constantly being rewritten. His contributions, once overlooked, are now being recognized as vital to the development of modern art. And perhaps, in time, he will no longer be the “forgotten Impressionist,” but rather, one of its most essential figures.

A Millionaire Who Painted for Himself

Unlike his peers, who had to sell paintings to pay rent, Caillebotte painted for the sheer love of it. While many of the Impressionists juggled financial instability with their creative ambitions, constantly worrying about finding buyers or securing exhibitions, Caillebotte remained untouched by these concerns. He had the unique privilege of painting exactly what he wanted, when he wanted, and for no one other than himself.

The Freedom of Wealth in a Starving Artist’s World

Born into wealth, Caillebotte never needed to cater to the tastes of bourgeois buyers. This financial freedom allowed him to experiment, unconstrained by market demands. His subjects weren’t dictated by commissions; they were chosen out of personal fascination. This is precisely why his work feels so different—there’s an intimacy, an unfiltered vision that wasn’t watered down for commercial appeal. His paintings don’t scream for attention or beg for approval; they simply exist, unapologetically authentic.

While other artists had to navigate the often fickle and conservative tastes of the Salon or convince collectors that their radical techniques were worth investing in, Caillebotte painted purely from instinct. He wasn’t bound by the rules of supply and demand, allowing him to develop an artistic voice that was entirely his own. He had no incentive to compromise, no reason to adjust his palette or style for financial survival.

The Burden of Privilege: A Double-Edged Sword

Yet, paradoxically, his wealth also made critics reluctant to take him seriously. After all, if you weren’t suffering for your art, were you even a real artist? The mythology of the starving artist had already begun cementing itself in the 19th century, and Caillebotte was an anomaly—a man who could create without consequence. To many, his financial stability made his artistic endeavors seem more like a hobby than a calling.

This question has long plagued art history, where the myth of struggle is often more revered than the art itself. There’s an unspoken belief that suffering somehow makes art more authentic, that desperation fuels genius. Caillebotte’s ability to focus solely on his craft should have been celebrated, but instead, it was held against him. He was, in essence, too lucky to be great in the eyes of the critics.

Even today, we see similar biases. Wealthy artists are often dismissed as dilettantes, their work perceived as lacking the gravitas that comes from hardship. Caillebotte, despite his undeniable talent and groundbreaking approach to perspective, was subtly pushed to the margins of Impressionism’s narrative—not because he lacked skill, but because he lacked struggle.

Caillebotte as a Patron: The Invisible Hand Behind Impressionism

His financial independence also allowed him to collect the works of his friends, becoming one of the most significant patrons of Impressionism. Without him, Monet, Renoir, and others might not have had the resources to continue their work. In this way, Caillebotte’s money wasn’t just his privilege—it was the scaffolding upon which Impressionism stood.

At a time when the art establishment largely rejected the Impressionists, branding their work as unfinished and chaotic, Caillebotte was not only buying their paintings but actively funding their careers. He purchased works from Monet, Sisley, Pissarro, and Renoir at times when their financial situations were dire. He supported exhibitions, encouraged experimentation, and quite literally kept the movement alive when commercial success seemed like an impossible dream.

Building a Legacy: The Collection That Changed Everything

Caillebotte didn’t just collect art for personal enjoyment—he was curating a future where the Impressionists would be recognized for their genius. His collection was vast, including some of the most iconic works of the era. When he died, he bequeathed much of it to the French state, leading to one of the most significant moments in the history of modern art.

However, even in death, his wealth complicated his legacy. The government initially resisted accepting his collection, hesitant to associate the state with such avant-garde works. They saw Impressionism as radical, a deviation from the accepted norms of academic painting. It took years of negotiation before a portion of his collection was finally accepted, and even then, it was heavily edited—some pieces were rejected, deemed too progressive for the public.

The Irony of Historical Recognition

Ironically, had Caillebotte struggled financially, had he suffered in a drafty Parisian garret, his work might have been taken more seriously in his own time. It wasn’t until decades later that he was recognized as both a formidable painter and a foundational figure in Impressionism’s success.

Today, his works are celebrated for their bold compositions, unique perspectives, and modern sensibility. His paintings of urban Paris, often featuring stark angles and unusual vantage points, feel almost cinematic, anticipating 20th-century photographic techniques. And yet, for too long, he was viewed more as a benefactor than an artist.

Reevaluating Caillebotte: Breaking the Myth of the Starving Artist

The art world’s obsession with struggle as a prerequisite for genius needs to be challenged. Caillebotte’s career proves that artistic brilliance isn’t dependent on financial hardship. If anything, his financial freedom allowed him to explore and experiment in ways that many of his contemporaries couldn’t.

His paintings are proof that passion, not poverty, is the true fuel of creativity. He painted not because he needed to, but because he wanted to—because he had something to say, something to observe, something to capture.

Perhaps it’s time we stop romanticizing suffering and start recognizing that privilege, when used wisely, can be just as powerful a force in shaping art history. Without Caillebotte, Impressionism might not have survived its most precarious years. His wealth was not a crutch but a tool—one that he used to shape the future of modern art in ways that still resonate today.

The Rich Painter Who Saw More Than Money

Gustave Caillebotte may have been a millionaire, but he was never just a collector or a financier. He was a visionary artist who painted with an uncompromising eye, a patron who believed in the avant-garde before the world caught up, and a man who proved that artistic dedication doesn’t have to come with suffering.

His paintings, now hanging in the world’s most prestigious museums, are a testament to what happens when an artist is free to create without limitations. He didn’t need to sell his work to survive—but perhaps that’s precisely why his work survives today.

And so, the next time someone tells you that great art is born from suffering, remind them of Caillebotte—the man who painted for himself and, in doing so, helped change the course of art history.

Analyzing the Art Style of Gustave Caillebotte

Caillebotte’s Unique Position in Impressionism

Gustave Caillebotte occupies a peculiar space in art history—too realist for an Impressionist, yet too modern for a strict academic painter. While his contemporaries, such as Monet and Renoir, focused on loose, quick brushstrokes to capture fleeting moments of light, Caillebotte approached painting with an almost photographic precision. His works are defined by their sharp perspective, architectural composition, and psychological depth. Unlike many Impressionists who painted en plein air, Caillebotte often worked indoors, using the city and its inhabitants as his primary subject matter.

The result? A body of work that feels strikingly contemporary, even by today’s standards. His unique approach to perspective, color, light, and brushwork set him apart from his peers, and his paintings capture the paradox of modernity—both its grandeur and its alienation.

Use of Perspective and Composition

One of the most defining aspects of Caillebotte’s art is his use of extreme perspective and bold compositions. His paintings frequently employ high vantage points, unusual angles, and a striking sense of depth. This approach was likely influenced by his background in engineering and architecture, as well as the advent of photography.

In Paris Street; Rainy Day (1877), Caillebotte masterfully uses perspective to create a dramatic, immersive cityscape. The sharply receding lines of the cobblestone street and the placement of figures in the foreground create a three-dimensional effect that pulls the viewer into the scene. Unlike traditional landscape compositions, which often center the viewer comfortably, Caillebotte’s works challenge our sense of space and perspective, making us feel like participants rather than mere observers.

Another example is The Floor Scrapers (1875), where the tilted floor and carefully placed figures create a sense of movement and physicality. The composition is not merely about depicting manual labor—it draws the eye dynamically through the painting, creating a visceral, almost cinematic effect.

Caillebotte’s Relationship with Light and Color

Unlike Monet’s obsession with shifting light conditions, Caillebotte approached light in a more structured and atmospheric manner. His use of subdued, often cool tones gives his paintings an introspective, almost melancholic quality.

In Man on a Balcony, Boulevard Haussmann (1880), the light is diffused, almost grayish, reflecting the cool urban environment rather than the golden hues typical of Impressionist landscapes. This careful modulation of light adds to the painting’s mood of detachment and observation, reinforcing the theme of urban isolation.

Caillebotte’s palette often leans toward muted blues, grays, and earth tones, setting him apart from the brighter, pastel-infused palettes of his contemporaries. This restrained use of color allows his compositions to feel elegant, understated, and eerily modern.

Themes in His Work: Modernity, Isolation, and the Urban Gaze

Caillebotte was fascinated by the modern city and its effects on individuals. His paintings frequently depict people looking out from windows or balconies, observing the world but remaining distant from it. This recurring motif suggests a sense of detachment, a feeling of being present but not fully engaged—a theme that would later be explored in the works of Edward Hopper and other 20th-century painters.

In Young Man at His Window (1875), a solitary figure stands at a window, his back turned to the viewer. The vast cityscape outside stretches endlessly, reinforcing the theme of modern solitude. Is the figure longing for something? Is he trapped in his bourgeois existence? Caillebotte leaves these questions open, allowing the viewer to project their own interpretations onto the scene.

Similarly, View from a Balcony (1880) places the viewer in a voyeuristic position, emphasizing the sense of distance between observer and subject. These works highlight Caillebotte’s keen ability to capture the psychological nuances of urban life and human isolation.

Brushwork and Surface Texture

Caillebotte’s brushwork is another area where he deviates from his Impressionist peers. While Monet and Renoir embraced loose, rapid strokes to create a sense of movement, Caillebotte’s approach was more controlled, precise, and deliberate. His surfaces often appear smoother, with a heightened sense of detail that aligns him more closely with Realism than pure Impressionism.

However, he was not entirely rigid. In paintings like Boating on the Yerres (1877), his handling of water and reflection shows a more Impressionist tendency—his brushstrokes become looser, capturing the fluidity and movement of water. This suggests that Caillebotte was not confined to a single style but rather experimented, adapting his technique to suit his subject matter.

His Influence on Later Artists

Despite being underappreciated for much of the 20th century, Caillebotte’s work has had a lasting impact on modern art. His use of bold perspective and urban themes can be seen in the works of later painters such as Edward Hopper, Giorgio de Chirico, and even early 20th-century photographers.

- Hopper’s compositions, with their themes of isolation and voyeuristic observation, echo Caillebotte’s balconies and windows.

- De Chirico’s metaphysical cityscapes, with their eerie emptiness and distorted perspectives, share a kinship with Caillebotte’s urban visions.

- Photographers like Brassaï and Cartier-Bresson, who captured the loneliness of city life, owe a debt to Caillebotte’s framing and perspective.

His rediscovery in the mid-20th century led to a reevaluation of his contributions, placing him firmly among the pioneers of modern urban realism.

Why Caillebotte Stands Apart

Gustave Caillebotte was never just another Impressionist—he was a painter of modern life, a master of perspective, and a psychological observer of urban existence. His work stands apart due to its:

- Meticulous attention to composition and perspective

- Use of controlled light and restrained color palettes

- Recurring themes of urban alienation and voyeurism

- Fusion of Realist precision with Impressionist spontaneity

- Influence on later artists and photographers

While history initially overlooked him, today, Caillebotte’s work is recognized for its groundbreaking approach and its ability to capture the complexities of modernity and the human experience. His paintings continue to resonate, proving that the sharp-eyed observer of 19th-century Paris was, in many ways, a visionary ahead of his time.

Ten Little-Known Facts About Caillebotte

- He was an early adopter of photography, using it to influence his compositions.

- He was obsessed with yacht racing and even designed his own boats.

- He once bought Monet’s paintings when no one else would, keeping the Impressionist movement afloat—literally.

- The Louvre rejected his art collection, considering it too radical.

- He experimented with extreme perspectives, a precursor to modern photography.

- He never married, devoting his time to art, sailing, and philanthropy.

- His will stated that his Impressionist collection should be donated to France—a decision they regretted ignoring.

- He painted from life, often depicting working-class subjects with an empathetic realism.

- His estate helped establish France’s first motorboat club.

- It took nearly a century for major museums to give him the recognition he deserved.

His Relationships, Personal Life, and Legacy

Gustave Caillebotte was more than just an Impressionist painter—he was a connector, a patron, and an essential force behind the movement’s survival and success. While his work has often been overshadowed by the more commercially celebrated Impressionists, his relationships with artists such as Monet, Renoir, and Degas were deeply influential. He was not only their peer but also their financial lifeline, providing the kind of support that allowed these artists to create freely without the suffocating pressures of commercial viability.

Caillebotte and Monet: A Friendship That Shaped Impressionism

Perhaps Caillebotte’s most significant artistic relationship was with Claude Monet. Monet, often regarded as the face of Impressionism, endured significant financial difficulties throughout his early career. He struggled to sell paintings, constantly moving in search of more affordable living conditions, and relied on patrons and collectors who saw the potential in his work. Caillebotte was one of the most steadfast of these supporters.

Their friendship was not built solely on financial support, though that was a major component. They shared an appreciation for the radical, light-infused approach to painting that defined Impressionism, and they often exchanged ideas. Caillebotte’s eye for composition and structure complemented Monet’s looser, more spontaneous brushwork. Monet’s letters reveal gratitude for Caillebotte’s unwavering belief in his work, and without Caillebotte’s purchasing power, it is possible that Monet’s legendary series of water lilies and haystacks might never have been realized.

Beyond purchasing Monet’s paintings when no one else would, Caillebotte also helped fund the development of Monet’s famous garden in Giverny. This was not a trivial contribution—Giverny would later become the source of some of Monet’s most celebrated works, serving as an endless well of inspiration. Caillebotte understood that Monet needed not just financial support, but also an environment in which to create freely.

A Patron and Confidant for Renoir and Degas

While Monet and Caillebotte shared a profound artistic alignment, Caillebotte’s relationships with Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Edgar Degas were equally important. Renoir, known for his sensuous, vibrant depictions of Parisian life, benefited greatly from Caillebotte’s financial assistance. The two artists also shared a fascination with contemporary Paris, often capturing the leisure and modernity of the city in different but complementary ways.

Caillebotte’s friendship with Edgar Degas was somewhat more complex. Degas, a fiercely independent and often combative figure, did not always get along easily with his fellow Impressionists. He was known for his sharp tongue and skepticism of artistic trends. However, he respected Caillebotte’s unique perspective, particularly his mastery of perspective and composition. Caillebotte’s paintings of the new Paris—its boulevards, working-class figures, and changing social dynamics—resonated with Degas, who was equally fascinated by movement and modern life. Their shared admiration for photography as an emerging medium also contributed to their bond.

The Impressionist Exhibitions: Caillebotte’s Organizational Genius

Caillebotte was not just a painter and collector; he was also a key organizer of the Impressionist exhibitions. While today we take for granted the prominence of Impressionist art, at the time, the movement was still struggling for legitimacy. The traditional French art establishment, dominated by the Salon, largely rejected the loose brushwork and unconventional perspectives of the Impressionists.

Caillebotte played a critical role in ensuring the success of these independent exhibitions. He not only helped finance them but also actively curated works, secured venues, and managed logistics. His strategic thinking helped shape the public perception of the movement, gradually pushing Impressionism from the fringes of the art world into the mainstream.

The Private Man Behind the Public Patron

Despite his public role as a patron and collector, Caillebotte was a deeply private individual. Unlike some of his peers, who relished the bohemian lifestyle of Paris, he preferred quieter, more solitary pursuits. He had a strong interest in gardening, yacht racing, and engineering—interests that further set him apart from the stereotypical image of the struggling, disheveled artist.

His love for yachting, in particular, was more than a mere hobby. He designed and built boats, demonstrating a meticulous precision that paralleled his artistic approach. Some of his paintings of boating scenes reflect this personal passion, capturing not only the movement of water but the intricate mechanics of the vessels themselves.

Despite never marrying, Caillebotte maintained close relationships with his family, particularly his brother Martial. His letters suggest a man who was affectionate and devoted but preferred to keep personal matters out of the public eye. Unlike Renoir or Degas, who left behind extensive personal correspondences filled with lively anecdotes, Caillebotte’s quieter nature means that much of his inner world remains speculative.

The Legacy That Took a Century to Acknowledge

For decades after his death, Caillebotte’s contributions to Impressionism remained overshadowed. His role as a patron often took precedence over his achievements as an artist. It wasn’t until the late 20th century that art historians began reassessing his work, recognizing him as a pivotal figure whose artistic output was just as revolutionary as his financial support.

Museums that once overlooked his work began hosting retrospectives, and his paintings—once considered secondary to Monet and Renoir—gained newfound appreciation. The Art Institute of Chicago, the Musée d’Orsay, and the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. all prominently feature his work today, showcasing his unique perspective on modern Paris.

The irony of Caillebotte’s legacy is that the very thing that ensured Impressionism’s survival—his wealth—was also what caused him to be overlooked as an artist. The myth of the starving, suffering artist is so deeply ingrained in art history that Caillebotte’s financial security almost disqualified him from being taken seriously. However, as more scholars revisit his paintings, it has become clear that his wealth was not a crutch but a tool that allowed him to create some of the most striking images of 19th-century Paris.

The Unsung Hero of Impressionism

Caillebotte was more than just a benefactor. He was an artist of extraordinary vision, a friend who lifted an entire movement, and a man whose contributions shaped the history of modern art. His paintings—so often structured yet emotionally rich—capture a Paris in transition, a city in motion, a world both intimate and impersonal.

His story serves as a reminder that artistic greatness does not always come from suffering. Sometimes, it comes from vision, support, and the ability to recognize and uplift genius in others. Without Gustave Caillebotte, Impressionism as we know it might not exist. And for that, the art world owes him an immense debt—one that is only now beginning to be fully repaid.