Émile Zola: The Novelist Who Painted with Words — Inside Les Rougon-Macquart and the Birth of Literary Naturalism

Picture this: a novelist who doesn’t just tell stories, but sets up mini-laboratories; who doesn’t simply observe society, but dissects it. That was Émile Zola — the man who turned the novel into an experiment, the family saga into a social panorama, and words into paint strokes of reality. His twenty-volume cycle Les Rougon‑Macquart (1871-1893) remains one of the great accomplishments of 19th-century literature: equal parts social science, visual art and narrative machine. In this section, we’ll explore how Zola crafted his style, why his cycle matters, and how he became the father of literary naturalism—a method, a manifesto and, let’s admit it, a bit of a show-off.

In doing so we’ll answer key questions: What is Zola’s “naturalist novel”? Why did he choose one family under the Second Empire as his subject? And how did his descriptive precision make literature look like painting? By the end of this section you’ll understand how the novelist who “painted with words” left his mark: on the novel, on art, and on modern culture.

1. The Laboratory of the Novel: Zola’s Naturalist Method

1.1 From Realism to Naturalism

-

Zola emerges in a literary world dominated by realism—but he wanted more than capturing manners and morals. He wanted causal chains, environments, heredity. According to Britannica, his naturalist goal was “demonstrating the deterministic influence of heredity and environment” through Les Rougon-Macquart.

-

He explicitly borrowed from the experimental sciences—medicine, biology—and delivered his essay Le Roman expérimental (1880) which argues the novelist is like a scientist: observe, hypothesize, test.

-

Naturalism, then, isn’t just style—it’s a program. Zola writes: “The novelist as the observer of nature and man under determined forces.”

1.2 Key Principles: Heredity, Environment & the Deterministic Chain

-

Zola believed characters are shaped not simply by will, but by heredity and environment (“milieu”)—a recurring trio of forces.

-

His subtitle for Les Rougon-Macquart says it: Histoire naturelle et sociale d’une famille sous le Second Empire (“Natural and Social History of a Family under the Second Empire”).

-

Practical implication: each novel of the cycle examines a different milieu (the mine, the store, the slums, the art world) but tracks how the same family lineage performs under those pressures.

1.3 The Novel as Experiment

-

Zola demanded his novel examine “how” things happen rather than “why.”

-

This means his prose often feels detailed, exact, almost forensic: newspapers, market halls, machines, workers all appear not just as background but as variables in a social test. For example, the mining scenes in Germinal function like a case study in suffering and revolt.

-

Yet: critics note the gap between theory and practice—Zola’s ambition was lofty, but his novels don’t always strictly follow the scientific method.

2. The Family Saga as Social Canvas: Les Rougon-Macquart

2.1 Why One Family? Why Twenty Novels?

-

Zola chose a single family, composed of two branches (the ambitious Rougons and the destitute Macquarts), to reflect the full sweep of society under Napoleon III.

-

The cycle covers multiple classes and settings—urban, rural, industrial—making the novel series a cross-section of Second Empire France. Britannica: “various members of the … family … Zola examines the impact of environment by varying the social, economic, and professional milieu.”

-

Twenty volumes = ambitious. It’s not just storytelling; it’s mapping.

-

Example: La Fortune des Rougon (1871) begins the genealogy in Plassans.

-

Example: Germinal (1885) pits miners vs. capitalism in epic scale.

-

2.2 Notable Novels in the Cycle & Their Milieus

| Novel | Year | Milieu | Theme |

|---|---|---|---|

| L’Assommoir (1877) | Working-class Paris | Laundry/slums | Alcoholism, survival |

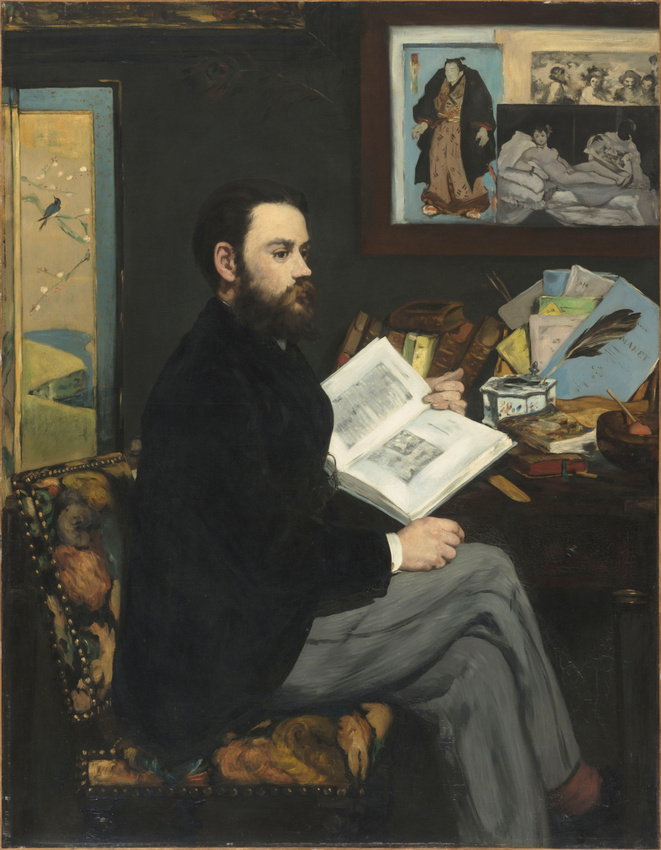

| Nana (1880) | Theatre/High society | Courtesan world | Decadence, sexuality |

| Au Bonheur des Dames (1883) | Department store | Capitalism, consumption | Modern commerce/social change |

| Germinal (1885) | Coal mines | Labor, revolt | Industrial conflict |

| La Bête humaine (1890) | Railways | Technology & violence | Heredity, madness |

2.3 Reading The Cycle: Approaches & Challenges

-

Choosing order: publication order (Zola’s timeline) vs. thematic order (by milieu).

-

Challenges: sheer scale (20 novels), language, translation quality.

-

Why bother? Because the full effect is cumulative: seeing how heredity + environment play out across generations amplifies the naturalist method.

-

Trivia: Zola originally proposed it in 1868.

3. Zola’s Style: Painting with Words

3.1 The Prose of Visual Realism

-

Zola’s writing is famously descriptive. He treated setting almost like character: the mine in Germinal, the store in Au Bonheur des Dames, the city in La Curée.

-

Britannica: his narrative “vivid paintings of crowds in motion lend authenticity and power” to his portraits of society.

-

What does this mean?

-

Long descriptive passages → sense of place and detail.

-

Use of color, light, machinery, sounds—he composes tableaux as a painter would.

-

He offers not just story but atmosphere, texture, and sensation.

-

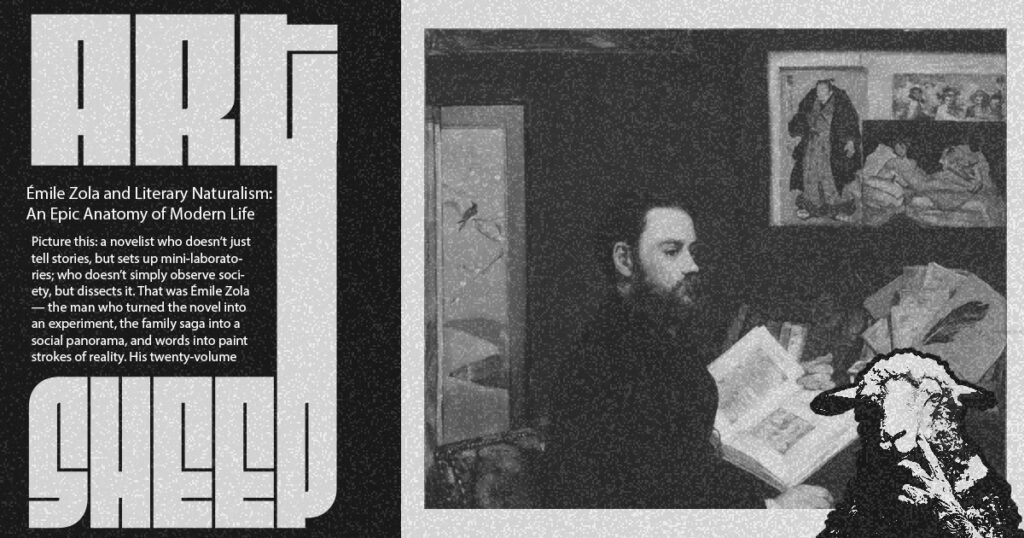

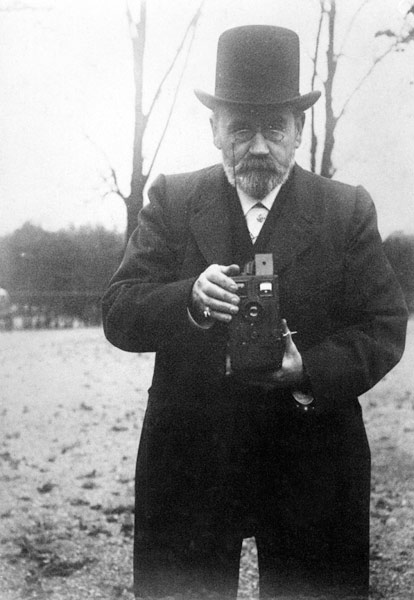

3.2 Visual Arts & Literature: Cézanne, Manet, Courbet

-

Zola was not isolated in a literary vacuum. He rubbed shoulders with painters—most notably Paul Cézanne, whose early style Zola praised. Their friendship later soured—L’Œuvre (1886) portrays an artist resembling Cézanne, leading to personal and artistic fallout.

-

Zola’s attention to visual detail echoes painting: “word-pictures of Paris transformed by varying effects of colour, light, and atmosphere.”

-

For Art-Sheep audience: this is gold. Connect Zola’s novels to visual art images (industrial paintings, Impressionist scenes) and show how his narrative style overlaps with painterly composition.

3.3 The Irony: Precision, Pessimism & Poetry

-

Zola sought scientific objectivity, yet his writing often spills into drama, metaphor, fatalism. As one critic notes, there is a “gap between theory and practice.”

-

Key paradox: Naturalism promised cold analysis but delivered human heat. The detail, the mechanics are there—but underneath pulses rage, injustice, emotion. That tension is central.

4. Why It Still Matters: Zola’s Relevance in 21st-Century Culture

4.1 From Text to Screen, Stage, Workplaces

-

Germinal, L’Assommoir, La Bête humaine have been adapted repeatedly—demonstrating the visual, dramatic power of Zola’s writing.

-

The “novel as social mirror” is a trend still alive—documentaries, graphic novels, even data-driven journalism owe a debt to Zola’s method.

4.2 Themes that Echo Today

-

Labor, extraction, environment – Germinal as mining novel = early literature of resource struggle.

-

Heredity, class, mobility – the social forces Zola studied remain with us in new forms (inequality, genetics, tech domination).

-

Media, spectacle, justice – Zola’s direct, polemical voice (see J’Accuse) prefigures modern media crises.

4.3 A Call to Read (or Re-Read) Zola

-

For readers: don’t treat Zola as dry classic. Approach him as one would immersive TV saga, or a visual feast.

-

Use his cycle as a lens to view modern society—then reflect on your own environment.

-

Engagement idea: Join a reading group of Les Rougon-Macquart.

-

Offer link or resource list to translations, annotated editions, visual pairings (for Art-Sheep readers).

Émile Zola may have lived in the 19th-century, but his ambitions were pre-modern-digital: map society, frame injustice, document reality with the precision of a microscope and the flair of a painter. Les Rougon-Macquart stands as his grand project, his declaration that “the novelist paints life” — and maybe that novelists should also change it.

If you’ve never ventured into this cycle, pick the milieu that intrigues you (mines, stores, art world) and dive in. Subscribe to Art-Sheep’s newsletter for our next section where we’ll explore “Germinal: Coal Dust, Labor Aesthetics & the Industrial Sublime”. Leave a comment: which Zola milieu would you choose first—and why?

The Family Experiment: Les Rougon-Macquart as a Mirror of Empire

Émile Zola’s ambition was monstrous — not in cruelty, but in scale. Twenty novels, one dynasty, and an empire in the background. Few writers before or since have dared to dissect a whole society by tracing the bloodlines of a single family. Les Rougon-Macquart is not just a novel series; it’s a vast X-ray of the Second Empire, a genealogy of greed, hope, madness, and decay. Each book stands alone, yet together they hum like one immense social organism, breathing the air of industrial Paris, rural Provence, and the glittering rot of high society.

Zola did not simply choose a family — he constructed one, engineered like a scientific model. The Rougon-Macquarts descend from one matriarch, Adelaïde Fouque, whose two sons, one legitimate and one not, seed two branches: the Rougons, ambitious and calculating; and the Macquarts, volatile, often crushed by poverty or vice. Between them, Zola mapped every stratum of society under Napoleon III — the bureaucrats, the merchants, the courtesans, the laborers, the mad, and the dreamers.

A Novel in Twenty Acts

Each installment of the cycle functions as both an individual study and a brick in the empire’s edifice. The books appeared from 1871 to 1893, spanning the optimistic dawn of modern France to the bruised aftermath of industrialization. Zola wrote them with almost pathological discipline, claiming he was “recording the Second Empire’s anatomy.” He wasn’t exaggerating.

In La Fortune des Rougon, the series’ first volume, he plants the family tree in the provincial soil of Plassans, a fictional stand-in for Aix-en-Provence. From there, the branches twist outward: L’Assommoir into the Parisian slums; Nana into the decadent theatres; Germinal into the black lungs of the coal mines; Au Bonheur des Dames into the cathedral-like department store; La Bête humaine onto the iron rails of progress.

Read consecutively, these novels unfold like a single panoramic fresco — a slow camera panning through every alley, salon, and factory of France. They reveal how the same hereditary impulses mutate under different environments. Lust turns to ambition, ambition to greed, greed to destruction. Zola’s genius is not moral judgment but observation: the novelist as biologist, cataloguing the species of human behavior under capitalism.

Heredity, Environment, and the Human Machine

Zola’s famous trinity — heredity, environment, and moment — governs everything. His people are not heroes but mechanisms: nerves, bloodlines, desires inherited and replayed through generations. This deterministic framework sounds cruelly scientific, but within it pulses immense sympathy. Zola never mocks the weak; he studies them with the sorrow of a physician who knows the diagnosis but cannot alter it.

In L’Assommoir, the heroine Gervaise falls from dignity to ruin through poverty and alcoholism, yet Zola’s gaze remains tender, never moralistic. In Nana, her daughter’s beauty becomes her weapon and her curse — a commentary on the commodification of flesh in the new capitalist order. The miners of Germinal revolt, fail, and are buried alive beneath progress, but their struggle glows with tragic nobility.

This obsession with environment was radical. Balzac had already catalogued social types, but Zola injected biology and sociology into the mix. The result was literature that aspired to science but resonated as art — novels that could be dissected in the Sorbonne and still make readers weep.

The Second Empire as Character

Zola’s true protagonist is not any individual but the Empire itself — a regime of spectacle, corruption, and speed. Paris, rebuilt by Haussmann, becomes the central metaphor: a city of gleaming boulevards concealing rot beneath the cobblestones. Commerce, politics, and pleasure intertwine, producing a society addicted to progress but haunted by collapse.

He saw Napoleon III’s France as a laboratory of desire: industrialists turning ambition into empire, workers crushed by machines, women using beauty as currency. In this world, morality bends to profit, and identity is fluid, shaped by circumstance. Reading Les Rougon-Macquart today feels eerily modern. Replace the coal mines with data farms, the department store with social media, and Zola’s deterministic model still applies.

Narrative Architecture and the Art of Continuity

What makes the cycle extraordinary is not only its concept but its execution. Each novel interlocks with the others through subtle cross-references — a cousin glimpsed in one story reappears years later in another, transformed by fate. This continuity creates a sense of living history: readers experience the family’s evolution as if watching time itself unfold.

Zola planned the entire architecture before writing a single page. His preparatory notes for each book ran into hundreds of pages: genealogies, maps, character sketches, even floor plans of buildings. He was building a world as meticulously as a 21st-century showrunner constructs a cinematic universe. And like any great series, the magic lies in the details — the recurring gestures, the echoes, the genetic déjà vu.

The Writer as Archivist of Modernity

Zola’s monumental project also served a moral purpose: to document a civilization intoxicated by its own progress. He saw industrialization as both miracle and menace. His depiction of the mine in Germinal or the store in Au Bonheur des Dames is more than setting; it’s metaphor for the human condition under capitalism — the machine that promises prosperity but devours those who feed it.

Through his family chronicle, Zola wrote the social biography of France itself. His Rougons rise with the Empire, feasting on speculation and privilege; his Macquarts sink under its weight, condemned by poverty and vice. Between them lies a nation struggling to define itself. The novels’ cumulative force exposes the illusion of progress — the idea that civilization advances while individuals suffer the same ancient tragedies of desire, envy, and greed.

Style as Substance

The critical cliché says Zola was a scientist with a pen, but that underplays his artistry. His descriptive power turns sociology into poetry. Streets hum with energy; bodies sweat; machinery shudders; food gleams; light pours. He writes the world as though painting it in oils.

Take the opening of L’Assommoir, where the heat of the laundry room becomes a living thing — steam, scent, labor, exhaustion. Or the grand store in Au Bonheur des Dames, where architecture becomes organism, devouring smaller shops like a capitalist leviathan. Zola’s precision is aesthetic: he wants you to see the glint of every coin, smell the coal, taste the dust.

This painterly language links him directly to his contemporaries in visual art — Courbet’s realism, Manet’s modernity, Cézanne’s structures. They all shared the same impulse: to see the world as it is, stripped of romantic haze, yet rendered with almost sacred attention.

Legacy of the Cycle

By the time Zola finished Le Docteur Pascal, the final installment, he had created more than literature — he had engineered an ecosystem. The Rougon-Macquart family stands as one of the boldest acts of artistic totality in modern letters. It anticipated the social novel of the 20th century, from Thomas Mann’s Buddenbrooks to John Galsworthy’s Forsyte Saga, and even the multi-generational storytelling of television today.

Yet what keeps Zola alive is not his theories but his compassion. Beneath the data and determinism lies a deeply human writer who believed understanding was the first step toward justice. His family of sinners, dreamers, and strivers mirrors our own — still wrestling with heredity, environment, and the ghosts of progress.

Zola and the Aesthetics of Truth — Art, Science, and the Anatomy of Modernity

For Émile Zola, the artist was not a dreamer but a diagnostician. He dissected society the way a surgeon dissects a cadaver — not out of cruelty, but curiosity. In an age intoxicated by scientific discovery, Zola fused the laboratory with the novel, transforming fiction into a method of inquiry. “I want to explain how a person behaves, just as a chemist explains a reaction,” he once declared. It sounds cold — but in Zola’s hands, the microscope became an instrument of empathy.

His work sits at the crossroads of art and science, literature and sociology, instinct and analysis. If Balzac mapped society through desire, Zola mapped it through cause and effect. He wanted to know why we act as we do — how love, greed, lust, and despair could be traced through bloodlines and environments. For him, the novelist was an experimental scientist of the soul.

The Naturalist Manifesto

Zola’s literary naturalism emerged from a grand intellectual project: to apply the scientific method to fiction. The 19th century was an age of positivism, of Comte and Darwin, of new faith in observation and proof. Zola seized that spirit and injected it into literature. His 1880 essay “The Experimental Novel” became the manifesto of naturalism — a declaration that the writer should observe, hypothesize, and verify, treating human behavior as a form of living data.

He rejected romanticism’s foggy idealism and realism’s polite restraint. His novels would not merely represent life — they would test it. The page became a laboratory table, the plot an experiment in cause and consequence. When Gervaise in L’Assommoir succumbs to alcoholism, it is not moral failure but chemical inevitability; when Etienne Lantier in Germinal joins the miners’ revolt, it is not heroism but environment meeting temperament.

Yet Zola was not as deterministic as he is often accused of being. Beneath his method lies moral vision: the belief that understanding human suffering scientifically could lead to social reform. Knowledge, for Zola, was compassion with structure.

Science and the Sublime

To read Zola’s descriptions is to feel the paradox at his core — the scientific gaze rendered with the passion of a mystic. His Paris is not just a setting but a living organism; his coal mine is a beast breathing underground. In this fusion of science and sublimity lies Zola’s aesthetic revolution.

He used factual precision to evoke emotional truth. The mechanical rhythm of the trains in La Bête humaine mirrors the obsessive logic of human desire; the rhythmic clatter of commerce in Au Bonheur des Dames becomes a hymn to modernity and its discontents. His realism transcends observation — it borders on hallucination.

Where his contemporaries saw data, Zola saw drama. He turned the dryness of report into the humidity of life. Every observation carries the weight of meaning: a factory’s smoke becomes the breath of capitalism; a bloodline, the metaphor of history. His realism was never sterile — it was sensual, physical, even erotic in its attention.

Truth as Artistic Duty

Zola’s obsession with truth was not scientific vanity — it was moral warfare. He believed the artist’s duty was to reveal, not to comfort. “A work of art is a corner of creation seen through a temperament,” he wrote, reclaiming subjectivity as part of truth itself. In his eyes, beauty was not decorative but diagnostic.

He despised hypocrisy, particularly bourgeois morality that hid behind religion or respectability. His writing stripped away those masks, exposing the machinery beneath. L’Assommoir scandalized polite society precisely because it refused to sanitize the poor. Nana shocked readers by showing sex as commodity and corruption as systemic. For Zola, art had to tell the truth even when the truth smelled bad.

This honesty made him both revolutionary and reviled. Critics accused him of vulgarity, of “putting sewage on the page.” Zola smiled. To him, sewage was life — and ignoring it was moral cowardice. He famously quipped that art should “put its hands in the dirt.” And so he did, lovingly.

Between Determinism and Compassion

At the heart of Zola’s project lies a tension that keeps his work alive: the pull between determinism and empathy. If heredity and environment shape everything, where does moral responsibility lie? Can anyone truly change?

Zola didn’t fully resolve this. Instead, he dramatized the paradox. His novels show people trapped by forces larger than themselves — biology, class, desire — yet still yearning for transcendence. Gervaise dreams of dignity; Etienne dreams of justice; Denise dreams of love within commerce. The tragedy lies not in their failure, but in the nobility of their attempt.

This dialectic between fate and freedom, science and soul, is what prevents Zola’s naturalism from becoming mechanical. He was too human to be a pure scientist, too rational to be a pure mystic. He lived between microscope and metaphor.

Zola and the Modern Gaze

Zola’s influence radiates across disciplines. In literature, he fathered generations of writers who saw fiction as social diagnosis — from Theodore Dreiser to Steinbeck to Orwell. In painting, his defense of Manet and the Impressionists marked a new critical sensibility: to see beauty in the ordinary, to turn observation into rebellion.

In journalism, his fearless realism found its ultimate expression in J’accuse…! — his open letter defending Dreyfus, which fused art, truth, and politics into a single moral act. Here, the aesthetic of truth became civic duty. For Zola, writing could no longer be decoration; it had to be resistance.

His scientific pretensions may have aged, but his moral urgency has not. In an era of misinformation, his faith in documentation feels prophetic. In a culture obsessed with surfaces, his devotion to the anatomy beneath feels revolutionary.

The Anatomy of Modernity

Zola’s art captures the modern condition — the collision of progress and alienation, of reason and desire. He saw how the machine age both liberated and consumed humanity. His novels pulse with electricity, locomotion, and appetite — a world that moves faster than its morals.

The modern reader recognizes the symptoms: social inequality disguised as meritocracy, spectacle replacing substance, the individual swallowed by systems. Zola’s 19th-century laboratories are our 21st-century algorithms. His scientific metaphors still diagnose the same human restlessness — the hunger for meaning in a mechanized world.

A Truth That Burns

Zola’s pursuit of truth came at a cost. His unflinching gaze alienated polite society and exhausted him personally. But he would not retreat. “The truth is on the march,” he wrote — a line that sounds both triumphant and tragic. The truth, for Zola, was never comfortable; it was radioactive.

He died in 1902, suffocated by carbon monoxide from a blocked chimney — an accident, some said; a political assassination, others suspected. It was a grotesque irony: the great purifier of air, asphyxiated by his own. Yet even in death, his clarity endured.

Zola remains one of those rare writers who made truth beautiful without softening it — who found poetry in pathology, compassion in dissection, and humanity in the statistics of pain. He painted life as it is, and in doing so, revealed what it could be.

Scandal, Justice, and J’Accuse: When Literature Became a Weapon

By the late 1890s, Émile Zola was not merely a novelist — he was an institution. A man whose pen had documented poverty, desire, greed, and faith with more scientific rigor than any historian. But nothing in his long career of social autopsies prepared him for what was about to unfold: a national psychodrama that would test the limits of truth, power, and art itself.

The Dreyfus Affair — a political scandal so grotesque it could have been written by Zola himself — erupted like a moral earthquake at the end of the 19th century. It began, as most catastrophes do, with a lie: a forged document, a convenient scapegoat, and a country too proud to admit its own rot.

The Birth of the Affair

In 1894, French Army Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish officer, was accused of selling military secrets to Germany. The evidence was flimsy, the motives xenophobic, and the trial — a theater of hysteria disguised as patriotism. Dreyfus was convicted and exiled to Devil’s Island, a hellish rock off the coast of French Guiana. France applauded.

But not everyone. A few lonely voices began to suspect that the real crime was not treason, but the cover-up. Among them, eventually, was Émile Zola — a man constitutionally incapable of keeping quiet when confronted with hypocrisy.

Zola had always been obsessed with justice. His novels bristle with the moral friction between truth and convenience, idealism and corruption. Yet even he could not have imagined how completely France — his France — would lose its mind over Dreyfus.

What the affair revealed was not simply anti-Semitism, but the anatomy of systemic deceit: a military that lied, a press that raged, a church that blessed, and a public that preferred myth over evidence. Zola saw in it the very social pathology he had spent decades diagnosing.

Zola Enters the Arena

By 1898, Zola had seen enough. With Dreyfus still rotting in exile and the real culprit, Major Esterhazy, quietly exonerated, Zola decided that fiction was no longer adequate. Truth, he realized, had to abandon the novel and enter the courtroom.

On January 13, 1898, the newspaper L’Aurore published an open letter on its front page, titled in enormous black capitals: J’ACCUSE…! The author: Émile Zola.

The letter was both forensic report and moral thunderbolt. Zola accused the highest ranks of the French military of a deliberate miscarriage of justice, of falsifying evidence, and of institutionalized racism. He named names — with surgical precision and zero hesitation.

“I accuse General Mercier of having made himself an accomplice in one of the greatest inequities of the century… I accuse the handwriting experts of false testimony… I accuse the War Office of conducting an abominable press campaign…”

Each line landed like a cannon blast. It was not simply a defense of one man — it was a declaration of war against lies themselves.

The Scandal Erupts

The backlash was instantaneous. Newspapers screamed for Zola’s head. He was denounced as a traitor, a heretic, a destabilizer of national unity. Mobs burned his effigy in the streets. The government charged him with libel.

He knew this would happen. He had expected it — invited it, even. Because for Zola, the real goal was not self-preservation but exposure. By putting himself on trial, he would force France to confront its own moral reflection.

During the proceedings, Zola faced jeers, threats, and relentless media slander. But he remained composed, speaking with the same meticulous calm that marked his novels. “The truth is on the march,” he told the court — and indeed, it was.

He was convicted and sentenced to a year in prison. To avoid arrest, he fled to England, living in self-imposed exile under gray skies and chronic homesickness. But history had already shifted. J’Accuse had detonated a bomb beneath the French Republic.

The Art of Outrage

There had been political scandals before, but none that so nakedly exposed the power of words. Zola’s letter was not merely a legal argument; it was performance art. It fused rhetoric, morality, and spectacle in a way that prefigured the modern media moment.

He understood something essential: that outrage, when channeled through precision, becomes poetry. J’Accuse was written with a journalist’s clarity, a novelist’s drama, and a prophet’s fury. It transcended its own context.

The essay’s structure — each accusation a rhythmic incantation — reads almost like verse. Zola was conducting not just an argument but a ritual of purification. His tone was cold, his sentences disciplined, but the underlying emotion was volcanic.

It was this blend of restraint and fire that made J’Accuse immortal. Even now, over a century later, the phrase itself has entered the lexicon of moral rebellion. Every modern whistleblower, every open letter of conscience, owes a silent debt to that morning’s headline.

Literature Steps Out of the Page

In defending Dreyfus, Zola redefined the purpose of art. Literature, he proved, was not merely the documentation of reality — it was an instrument capable of reshaping it. His act bridged aesthetics and ethics, page and street, fiction and revolution.

Until then, the writer’s role had been largely observational: to illuminate injustice, yes, but from a polite distance. Zola shattered that illusion. He leapt into the fire.

In doing so, he paid a price. His health declined; his reputation split in two. Half of France revered him as a saint of truth, the other half reviled him as an enemy of the nation. Yet the real triumph was subtler: he had turned the novelistic ethos — empathy, observation, moral rigor — into direct political action.

Zola’s courage galvanized others. Intellectuals, writers, and journalists began to see that their pens could be weapons of justice, not just ornaments of intellect. The intellectuel engagé — the “engaged intellectual” — was born that year. From Sartre to Baldwin, from Orwell to Arundhati Roy, the lineage begins with Zola’s fury.

The Science of Injustice

It is tempting to see J’Accuse as a purely emotional explosion — righteous anger, moral passion. But that misses the precision of Zola’s attack. It was not sentiment; it was science applied to corruption.

Just as he had dissected social mechanisms in his novels, he dissected the anatomy of deceit in the Dreyfus Affair. He identified how authority feeds on fear, how prejudice disguises itself as patriotism, how bureaucracy metastasizes into moral paralysis.

He even used the same method as in The Experimental Novel — observation, analysis, conclusion. Only now, his subjects were not miners or shopkeepers but generals and ministers. Zola had moved from the laboratory of fiction to the operating room of politics.

This transition from art to activism was not an abandonment of literature but its evolution. In a sense, the Dreyfus Affair was the final volume of Les Rougon-Macquart: the ultimate case study of hereditary corruption, not in a family, but in a nation.

The Aftermath — and the Cost of Truth

Zola’s intervention changed everything. Public opinion began to shift. The real culprit, Esterhazy, was eventually exposed, and Dreyfus was exonerated in 1906. But Zola would not live to see that day.

He died in 1902, poisoned by carbon monoxide from a blocked chimney. Officially, it was an accident; unofficially, many suspected assassination. The French government investigated, as governments do, and found nothing.

The irony was almost biblical: a man who spent his life clearing the air, literally suffocated by it. Yet even in death, Zola’s breath continued to circulate. His funeral drew massive crowds, and when his remains were later moved to the Panthéon, the inscription beneath his name read simply: “Truth has entered the Pantheon.”

The Legacy of J’Accuse

What remains astonishing is how contemporary Zola’s act still feels. In an era of manipulated narratives, deep fakes, and information wars, J’Accuse reads like a prophecy. It reminds us that outrage, when tethered to evidence and integrity, can still ignite revolutions.

Modern journalism borrows his template — the open letter, the exposé, the signature as defiance. Every time an artist or writer risks reputation for principle, Zola’s ghost nods in approval.

His moral clarity wasn’t naïve idealism. It was disciplined empathy — the belief that truth, like art, must disturb before it heals. He understood that corruption thrives in silence, and that breaking that silence is itself a creative act.

Zola’s transformation — from novelist to moral insurgent — proved that art and ethics are not parallel lines but intersecting forces. And that intersection, however volatile, is where civilization renews itself.

When Literature Became a Mirror

Ultimately, J’Accuse did not just save a man — it saved France from itself. It forced a nation intoxicated by its myths to confront the poison beneath. It revealed the moral schizophrenia of modernity: a society that worships justice while practicing prejudice.

In that sense, Zola’s letter was more than a political intervention. It was a mirror. It forced readers to ask the most dangerous question: What would I have done?

And perhaps that is why J’Accuse still resonates. It speaks not to a specific scandal but to the eternal temptation of convenience over courage. The forms of injustice change; the psychology remains the same.

Zola’s genius was to recognize that truth, like beauty, must be dramatized to be seen. His masterpiece was not a novel, but an act — a performance of conscience so fierce it rearranged history.

Zola’s Resurrection — The Writer Who Refused to Die

When Émile Zola died in 1902, Paris wept, cheered, and whispered. He was both martyr and menace, prophet and heretic. Carbon monoxide may have killed the man, but not the phenomenon. Zola didn’t vanish — he multiplied. His words, his fury, his forensic humanity — they slipped into the bloodstream of Western culture, altering its DNA.

In the years that followed, the world kept returning to him — sometimes to canonize, sometimes to curse, but always to reckon. Few writers have ever so thoroughly infected history with their conscience.

The Man in the Smoke

Zola’s death was as symbolically theatrical as his life. The blocked chimney that asphyxiated him became an instant metaphor: the silencing of truth, the suffocation of reason, the literal choking of a voice that had insisted on clarity. France, still divided between Dreyfusards and anti-Dreyfusards, couldn’t even mourn him without arguing.

His funeral turned into a national psychodrama. Tens of thousands marched behind the coffin; others hissed from the sidewalks. There were flowers and jeers, prayers and slurs — a portrait of a country trying to bury both its guilt and its prophet.

But prophets never stay buried. Zola’s ghost lingered in every debate about justice, every artist’s crisis of responsibility. Even his enemies couldn’t get rid of him. They invoked him to attack others — “Don’t play the Zola” became shorthand for those who dared to speak truth too loudly.

Entering the Panthéon

In 1908, six years after his death, Émile Zola’s remains were transferred to the Panthéon — the marble sanctuary of France’s “immortals.” It was a symbolic victory, but also a paradox. The same Republic that once branded him a traitor now embalmed him as a national treasure.

As his coffin entered, Alfred Dreyfus — the man whose innocence Zola had defended — stood among the crowd. A royalist extremist attempted to assassinate him. The bullet missed. History’s sense of irony remained intact.

The inscription beneath Zola’s tomb reads:

“Truth has entered the Panthéon.”

It could just as easily have read: “So has discomfort.”

Zola’s presence there is a permanent irritant — a reminder that heroism often arrives wearing the face of disobedience. The marble calm of the Panthéon can’t quite contain his volcanic energy. You can almost hear him, restless beneath the stone, whispering his lifelong command: “Look harder.”

The Gospel of the Real

Zola’s resurrection didn’t happen through monuments but through influence. He invented a way of seeing that still defines modern art, cinema, and journalism.

His belief that art should be an autopsy of life — unflinching, empirical, human — became the foundation of realism as we know it. Before Zola, literature often moralized; after him, it analyzed. The sentimental novel became obsolete. Reality, with all its blood and contradictions, took center stage.

Naturalism, his literary manifesto, wasn’t just about observation — it was about responsibility. To depict life truthfully was to confront the systems that deform it: poverty, patriarchy, capitalism, the state. Zola didn’t separate beauty from brutality; he showed that one produces the other.

You can see his fingerprints everywhere. In George Orwell’s working-class chronicles. In Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath. In Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle. In the neorealist films of De Sica and Rossellini. Even today, every photojournalist documenting human suffering is, knowingly or not, Zola’s heir.

He taught art to sweat.

Zola the Prototype — The First Modern Writer

Zola was the first writer to understand fame as a medium. He didn’t just publish books; he curated public scandal. He knew that to move a society, you have to disturb it. He staged himself — not vainly, but strategically — as the conscience of France.

In this sense, he was both author and performance artist. His public readings were events. His letters were spectacles. His trials were theater. He blurred the line between artist and activist long before the word celebrity meant anything.

That fusion — of moral urgency and media fluency — makes him the prototype of the 20th-century writer. Without Zola, there is no Sartre, no Camus, no Baldwin, no Hitchens. He invented the template of the intellectual as public combatant: articulate, inconvenient, indispensable.

Truth’s Favorite Heretic

To read Zola today is to experience a strange mixture of awe and unease. His faith in truth feels almost utopian in our algorithmic age — as if he belonged to a civilization that still believed in facts. But his defiance feels more necessary than ever.

He reminds us that truth is not a discovery; it’s a discipline. It requires endurance, not innocence. His courage didn’t come from purity, but from fatigue — the exhaustion of pretending not to see.

In a century where information is cheap and conviction is expensive, Zola’s example feels radical again. He didn’t simply “speak truth to power.” He forced power to stutter.

And yet, his defiance was never nihilistic. He was not a cynic but a moral empiricist — someone who believed that if you illuminated the disease, you could still heal the patient.

This, ultimately, was Zola’s heresy: not disbelief, but too much belief — in reason, in justice, in the possibility that literature could civilize the world.

The Resurrection in the Digital Century

What does Zola mean to us now, in an era where outrage is ambient and everyone has a platform? Perhaps that sincerity still matters. That art without consequence is decoration.

Every viral exposé, every open letter, every investigative documentary carries his DNA. The courage to name names, to risk reputation for truth — that’s Zola’s voice echoing through time.

But there’s a deeper resurrection happening, too. Readers and scholars have begun to rediscover Les Rougon-Macquart not just as historical documents, but as eerily contemporary works — premonitions of capitalism, environmental crisis, and social alienation. Zola’s Paris was our planet before the apocalypse.

His miners in Germinal are today’s gig workers; his corrupt financiers in L’Argent are the algorithmic traders of Wall Street; his nervous, self-conscious bourgeois are the doomscrollers of Instagram. The machinery changes, the suffering does not.

Zola saw it all coming — the commodification of morality, the industrialization of illusion. That’s why his novels still sting. They’re not period pieces; they’re diagnoses without expiration dates.

Between God and the Microscope

In the end, Zola’s resurrection is philosophical. He replaced divine judgment with human accountability. His religion was observation; his sacrament, empathy.

But unlike the positivists of his time, he never lost his sense of wonder. His realism wasn’t mechanical — it was sacred. To describe a coal miner’s sweat, a laundress’s hands, a lover’s despair — this was, for him, a form of prayer.

He didn’t worship nature as idyllic, but as indifferent — a god that doesn’t forgive. His novels throb with that tension between determinism and desire, between biology and will. He believed that humans were trapped in systems — yet capable of transcending them through consciousness.

That paradox — bleak yet luminous — is what keeps Zola alive.

The Writer Who Refused to Die

There’s a quiet moment in Le Rêve where a character whispers: “Only those who burn live forever.” Zola burned. He burned through censorship, through hypocrisy, through the illusions of polite society. He turned art into combustion.

That’s why he refuses to die. He remains — stubborn, radiant, inconvenient — in the corner of every conversation about what art owes to truth.

If Balzac catalogued society and Flaubert perfected its language, Zola electrified it. He didn’t just portray the human condition — he indicted it. And in doing so, he liberated the novel from sentimentality and made it dangerous again.

In 1902, the smoke took him. But his breath — the moral oxygen of modern literature — remains. Every artist who insists that empathy is political, every journalist who risks exile for honesty, every reader who demands that beauty tell the truth — all of them are, whether they know it or not, breathing Zola’s air.