Beginning in 1938, the threat of war prompted a large-scale evacuation of France’s public art collections. The storage sites chosen for works of art were châteaux, tranquil locations in the heart of the French countryside, far from strategic targets, and thus escaping the imminent danger of bombing.

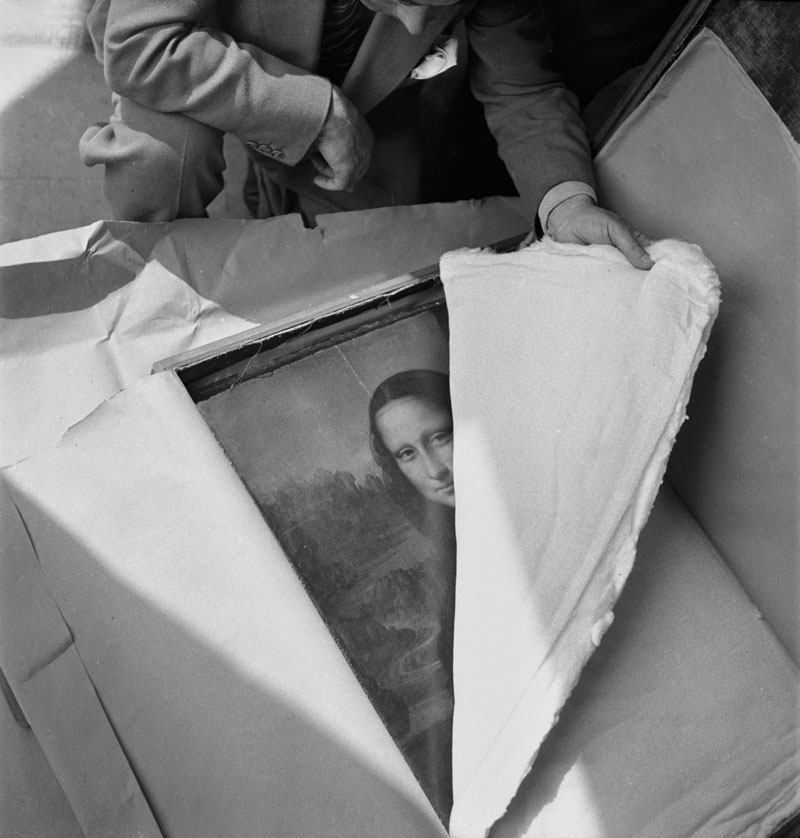

On August 28, 1939, the Mona Lisa left the Louvre and on September 3, as war had been declared, a decision was taken to ensure that all of the most precious works would leave the premises by the end of the day.

During the war, Leonardo da Vinci’s smiling maiden would move another five times before being brought back safe and sound. It was an unprecedented journey for the world’s most famous painting.

Moving the Winged Victory of Samothrace

On the Road

Stowed away in several hundred crates; sculptures, decorative objects and 3,690 paintings took to the road. The journey was a logistical feat of packaging and truck loading. The routes of France soon thronged with thirty-seven convoys joining the crowds already leaving the city.

The event was also an opportunity to view, often with unprecedented closeness, the museum’s most iconic works, suddenly brought down from their pedestals: the Winged Victory of Samothrace before it was sent to the Château de Valençay, the Venus de Milo or the Mona Lisa, which would be moved first to Chambord, then Louvigny, the Abbaye de Loc Dieu, the Musée de Montauban and finally to Montal, with the Louvre’s other paintings.

Jacques Jaujard, director of the Musées de France at the time, had the unenviable task of supervising the movements of these stored works, continually under threat from the hazards of an encroaching war. [Source: louvre.fr]

Preparing Venus de Milo for transport

The [German Occupied] Show Must Go On

The Louvre during the Second World War was still a palace at the heart of a capital having experienced one of the longest and most dramatic occupations in its history. The German authorities, eager to return the city of Paris to a semblance of cultural life, ordered the reopening of the museum in September 1940.

This partial opening was merely symbolic, with itineraries indicated in German and many of the galleries and viewing rooms completely empty and abandoned. The signs of war were everywhere: ornamental gardens transformed to grow vegetables, damage caused by nearby bombings, etc. [Source: louvre.fr]

German Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt at the Louvre

Name of Rembrandt painting in chalk where the artwork once hanged

The Grande Galerie of the Louvre, empty

The ‘Louvre Sequestration’

During the war, the Nazis plundered works of art from private collections belonging to prominent Jewish families or art dealers. They were meticulously wrapped and protected in preparation for their departure to Germany. This process unfolded in the galleries of the Louvre devoted to Near Eastern antiquities. The area was requisitioned by the Nazis and quickly rendered inaccessible to museum personnel.

After the Nazis seized the Jeu de Paume, which would be used as a further repository for looted works of art, the Louvre sequestration nevertheless continued, occasioning a continual to and fro of art works between both museums, with the result being that Jacques Jaujard was unable to prevent the transfer to the Third Reich of the stolen paintings. [Source:louvre.fr]

Cataloging stolen artworks during the Louvre Sequestration

Loading Peter Paul Rubens’ Marie de’ Medici cycle series

Masterpieces on the Move

Francisco de Goya’s Time and the Old Women

After the War, a new Louvre, transformed by major renovation work and gradually opened to the public between 1945 and 1947. Thanks to the skills and tenacity of those responsible for safeguarding cultural property, all of the museum’s major masterpieces returned to the palace, virtually unscathed.

via:http://twistedsifter.com