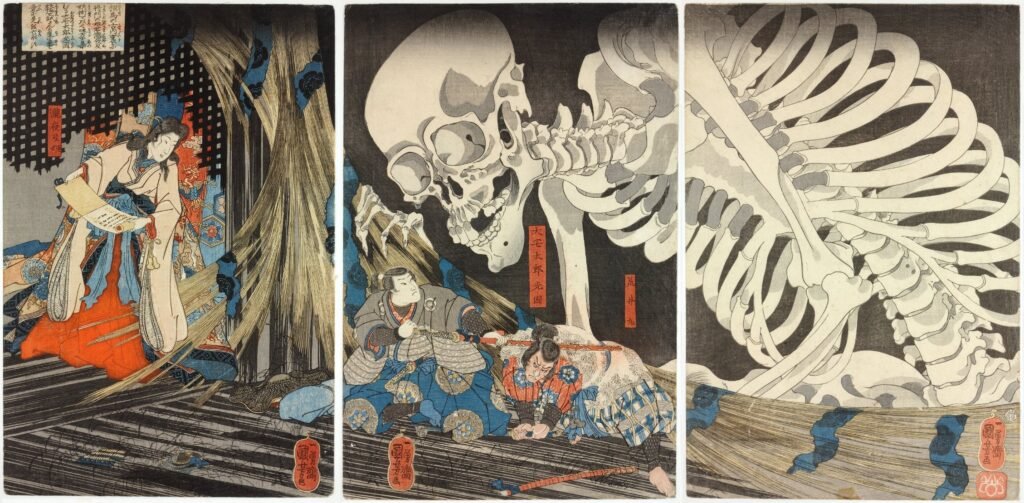

Before modern graphic design discovered flat color, before poster art discovered bold contour, before painters learned to crop reality like a camera — Japanese woodblock artists were already doing all of it with knives, blocks, and disciplined imagination.

Ukiyo-e — “pictures of the floating world” — did not just document a culture. It redesigned visual thinking.

Flatness as Power

Western art historically worshipped depth: perspective, illusion, dimensional modeling. Ukiyo-e rejected that priority. It embraced flat planes, decisive outlines, and color fields that read instantly.

This was not primitive. It was efficient.

Flatness turns image into symbol faster than realism ever can. That’s why modern visual culture — logos, posters, interface icons — unknowingly speaks ukiyo-e fluently.

Cropping Before Cameras

Woodblock masters cropped boldly. Figures cut by the frame. Diagonal compositions. Asymmetry as structure. When photography later introduced similar framing, Western audiences called it modern. The Japanese printmakers had been doing it for decades.

Masters like Hokusai and Hiroshige treated composition like choreography rather than window — a philosophy preserved and studied extensively in institutions such as The British Museum’s Japanese print collection.

Repetition Without Boredom

Because woodblocks are reproducible, variation became artistic rather than mechanical: color runs, edition shifts, seasonal versions. Repetition turned into controlled diversity.

This logic — serial variation — later shaped everything from pop art to contemporary printmaking.

Influence That Changed Europe

When Japanese prints reached Europe in the 19th century, they detonated quietly. Impressionists and post-impressionists borrowed compositional strategies immediately. Van Gogh copied them outright — respectfully, obsessively.

The West didn’t just admire ukiyo-e. It rewired itself through it.

Why It Still Feels Modern

Ukiyo-e feels contemporary because it is structurally aligned with how modern eyes process images: fast, bold, symbolic, cropped, color-driven. It speaks in visual shorthand without becoming simplistic.

You can still see its DNA in contemporary graphic satire and symbolic illustration — including modern conceptual visual work featured on Art-Sheep’s contemporary illustration spotlights — where flatness and metaphor outrank realism.

The Floating World Never Sank

The “floating world” was meant to describe fleeting pleasure — theater, beauty, fashion, city life. Ironically, its images became permanent.

Woodblock prints were supposed to be popular culture.

They became art history.

And modern visual language is still quietly borrowing from them — daily — often without knowing it.