The Wave That Conquered the World

When Katsushika Hokusai carved The Great Wave off Kanagawa sometime in the early 1830s, he probably wasn’t trying to create the world’s first global meme. Yet, nearly two centuries later, that’s exactly what happened. The Great Wave has become a symbol so omnipresent that it has outgrown art history and entered mass consciousness. It’s printed on tote bags, tattoos, emojis, corporate logos, skateboards, coffee mugs — even projected onto skyscrapers during climate protests. Somewhere between fine art and pop iconography, Hokusai’s wave stopped being just a wave. It became the image of an idea — the eternal clash between nature and humanity, chaos and order, tradition and modernity.

But before it was an icon, it was just ink and wood. And a man in Edo (modern Tokyo) who couldn’t stop drawing.

A Wave, a Mountain, and a Moment in Time

Hokusai’s The Great Wave off Kanagawa is part of his famous series Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji — a collection of woodblock prints (ukiyo-e) created between 1830 and 1833. The wave itself isn’t just a wave; it’s a performance. In its claw-like form, we can almost hear the roar of the sea and sense the helplessness of the fishermen below, their boats seconds away from being swallowed. In the distance, Mount Fuji stands calm, stoic, almost indifferent.

It’s the ultimate juxtaposition — motion versus stillness, ephemerality versus eternity. Hokusai gives us not a snapshot but a cosmology. The wave seems alive, animal-like, and yet precisely designed, each line cut with the discipline of a monk and the audacity of a rebel.

The irony? This print — so famous for its “Japanese” essence — was made possible thanks to Western Prussian blue pigment, recently imported through trade routes. It’s global before globalization, hybrid before hybridity became cool.

When Nature Becomes the Main Character

In The Great Wave, humans are not the focus. They’re fragile, nearly invisible, swallowed by the natural forces around them. It’s a perspective that feels especially modern — or perhaps timeless. Where Western painting of the same era (think Romanticism) often glorified the individual confronting nature, Hokusai stripped the ego out of the frame. His people don’t conquer; they endure.

This humility before the elements was deeply rooted in Japanese spirituality — Shinto’s reverence for nature and Buddhism’s meditation on impermanence. But it also reflected Hokusai’s personal worldview. The artist saw divinity in the mundane, transcendence in repetition. He once wrote that by the time he reached 70, he was beginning to understand form and that if he could live to 100, he might finally become a true artist. He died at 88, still chasing perfection.

In The Great Wave, that striving feels eternal. The print is almost cinematic — a still image vibrating with energy, suggesting that even stillness is never still.

The Birth of a Global Icon

For decades, The Great Wave existed as part of the ukiyo-e culture — prints made for mass consumption, sold cheaply in the streets of Edo. They were not luxury art pieces; they were everyday images, designed for the people. Ironically, it’s this reproducibility that set the stage for its later fame.

When Japan opened to the West in the mid-19th century, its art flooded Europe. Artists like Monet, Van Gogh, and Degas discovered Japanese prints and fell in love with their flatness, their abstraction, their daring sense of composition. Hokusai’s influence can be traced in Impressionism, Art Nouveau, and even Cubism. The movement that emerged — Japonisme — became one of the most significant cultural infusions in Western art history.

By the early 20th century, The Great Wave had crossed every border imaginable. It became shorthand for “Japan,” but also for art itself — the visual equivalent of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony or Shakespeare’s Hamlet. A universal code, recognizable even by those who have never heard of Hokusai.

From Sacred Print to Pop Commodity

Fast forward to the 21st century: Hokusai’s wave is everywhere. It’s on phone cases, beer cans, NFT drops, and corporate campaigns trying to look “artsy.” It’s been remixed into parodies of political leaders, climate change imagery, even Simpsons memes.

And yet, something about the wave resists trivialization. Even after being copied, twisted, commercialized, and memed into oblivion, it still carries a pulse. Maybe because its message — awe, fear, beauty, the sublime indifference of nature — remains painfully relevant. The wave’s power feels prophetic in the age of ecological collapse. It’s almost as if Hokusai’s print anticipated our collective anxiety — the smallness of humans before forces we can’t control.

In that sense, The Great Wave is the perfect artwork for the Anthropocene: it reminds us that nature doesn’t need us, but we desperately need it.

The Irony of Immortality

What makes The Great Wave so fascinating is how its meaning shifts with time. In Hokusai’s day, it was a humble landscape print. In post-war Japan, it became a symbol of national identity. In global culture, it’s an aesthetic — minimalist, powerful, endlessly reproducible.

It’s also, in a way, a tragedy. Hokusai, who lived in poverty most of his life, probably never imagined that a single print would become a billion-dollar image economy. Like Van Gogh’s Starry Night, it’s an artwork whose success arrived centuries too late for its creator.

But there’s something beautifully poetic about that too — a man who called himself “The Old Man Mad About Drawing” ended up shaping modern visual culture more profoundly than almost anyone else. His obsession became immortality.

Beyond the Wave: What Hokusai Really Taught Us

At its core, Hokusai’s legacy isn’t just about a wave, a mountain, or Japan. It’s about persistence — the radical belief that art can be both deeply personal and universally understood. He blurred the boundaries between high and low art, between sacred and commercial, between the individual and the cosmic.

That’s why his wave continues to resonate — not because it’s old or exotic, but because it captures the human condition: small, fragile, awe-struck, yet endlessly creative in the face of chaos.

In the end, The Great Wave didn’t just conquer the world. It conquered time.

And like any true masterpiece, it doesn’t demand understanding. It just keeps moving — quietly, endlessly — through every generation that dares to look long enough to see beyond the surface.

Hokusai Before Hokusai

The Many Lives of the Man Who Refused to Stay Still

Before there was The Great Wave, before he became a global symbol of “Japanese art,” before the museums, memes, and mugs, there was just a restless man with ink-stained hands and an almost pathological obsession with reinvention.

Katsushika Hokusai wasn’t born a genius — he built himself into one, name by name, sketch by sketch, failure by failure. Over his 88 years, he changed his artistic pseudonym more than 30 times, moved homes more than 90, and reinvented his style so often that he might as well have been multiple people sharing the same body.

To understand Hokusai’s genius, one must meet him before Hokusai — before the legend, before the wave, before history fixed him into one image. Because in truth, Hokusai was never one thing. He was the art world’s first shapeshifter.

Apprentice, Drifter, Rebel

Hokusai was born in 1760 in Edo (modern-day Tokyo), at a time when Japan’s cultural scene was booming under the Tokugawa shogunate. Ukiyo-e — literally “pictures of the floating world” — was the pop culture of the day: woodblock prints depicting kabuki actors, courtesans, landscapes, and everyday life. It was the art of pleasure and impermanence — accessible, affordable, and slightly scandalous.

Young Hokusai began as an apprentice to a woodblock engraver before joining the studio of Katsukawa Shunshō, a well-known artist who specialized in actor portraits. For a while, Hokusai painted exactly what the market demanded: celebrities of the stage, romanticized beauties, fleeting amusements of the floating world. But the obedient student didn’t last long.

When his master died, Hokusai was expelled from the studio — apparently for experimenting with styles outside the Katsukawa school. It was the first of many acts of defiance. The outcast picked up his brushes and started over, quietly plotting his artistic rebellion.

That moment — rejection by the establishment — would define his life. Hokusai didn’t just evolve; he mutated. Every setback became an opportunity for reinvention.

The Man with Many Names

Throughout his career, Hokusai used more pseudonyms than some people use hashtags. Tetsuzō, Sōri, Katsushika Hokusai, Taito, Iitsu, Manji — each alias marked a new phase, a new identity, a new obsession. It wasn’t a gimmick; it was a philosophy.

In the rigid hierarchies of Edo Japan, where birth and class defined destiny, Hokusai found freedom in fluidity. Names became his way of shedding skin, a ritual of rebirth.

Some of his names even referenced transformation: “Iitsu” meaning “one again,” “Manji” (used in his later years) referring to the Buddhist symbol of infinity. The man was literally branding himself with the idea of eternal change.

Each persona brought a shift in subject and style — from actor portraits to landscapes, from erotic shunga to mythological scenes, from fine art to manuals on drawing. It’s as if he refused to commit to one identity, anticipating the modern artist’s need for constant reinvention centuries before Warhol or Picasso made it fashionable.

Art as Labor, Life as Experiment

Hokusai was, above all, a worker. He produced tens of thousands of drawings, sketches, and prints. He designed picture books, illustrated novels, made posters, and taught hundreds of students. There was nothing romantic about his art in the modern sense — no patronage, no galleries, no myth of the isolated genius. Just endless, disciplined, obsessive creation.

He once said, “From the age of six, I had a mania for drawing. By fifty, I had published countless designs, but I am not satisfied.” He promised that at seventy he’d begin to understand nature, and by a hundred he’d finally become a true artist.

He died at eighty-eight, still unsatisfied. That restlessness wasn’t frustration — it was faith. A belief that perfection isn’t an end but a process, a never-ending apprenticeship.

If there’s a lesson in Hokusai’s life before The Wave, it’s this: genius isn’t born; it’s cultivated. Slowly, painfully, obsessively. Art wasn’t his escape from reality — it was his way of surviving it.

The Ukiyo-e Outsider

What made Hokusai different from his contemporaries wasn’t just his technical skill — it was his subject matter. While other ukiyo-e artists stuck to the glamorous world of courtesans and kabuki stars, Hokusai wandered into the countryside, sketching farmers, fishmongers, waterfalls, and ghosts.

He democratized beauty. He brought the sublime into the ordinary, the spiritual into the street. His fascination with nature wasn’t decorative; it was metaphysical. Every leaf, wave, and bird pulsed with meaning.

This outsider instinct also extended to his social life. Hokusai was poor, eccentric, constantly moving — sometimes out of poverty, sometimes out of superstition that his home had become unlucky. He lived among artisans, monks, and the poor, yet his art spoke a language the elite couldn’t ignore.

He was the visual poet of Edo’s underbelly — a man who saw the infinite in the mundane and made it sing in indigo and line.

The Turning Point: Books, Manuals, and Madness

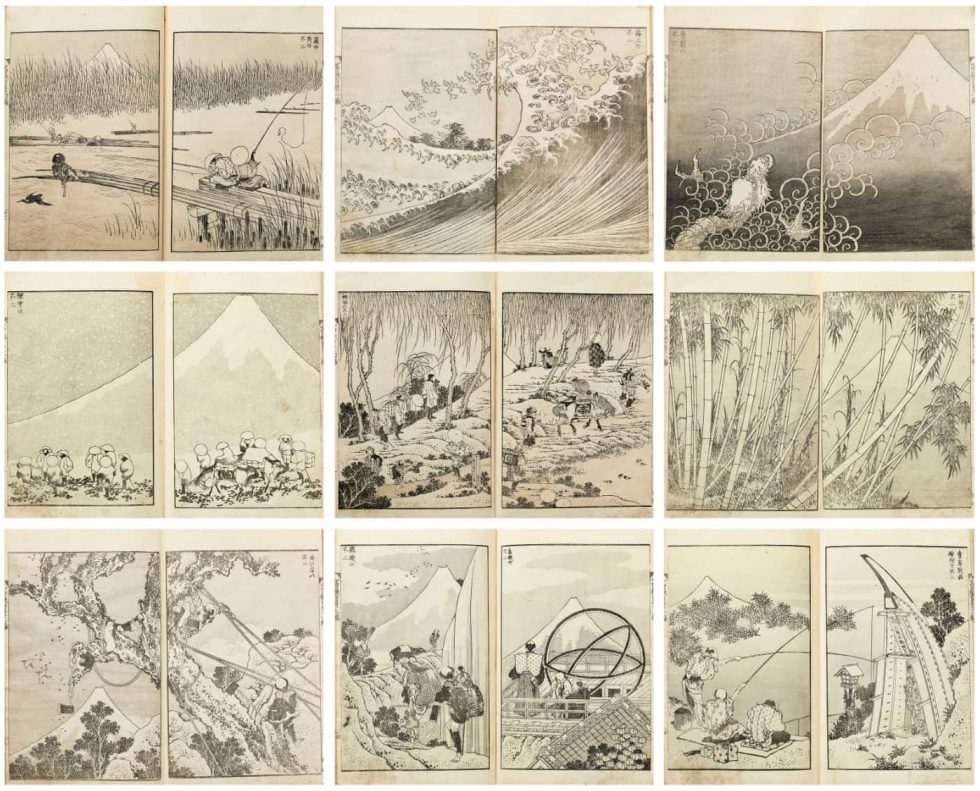

Before The Great Wave came Hokusai Manga — a series of sketchbooks filled with drawings of people, animals, demons, and landscapes. Published in 1814, it became a sensation. Think of it as the 19th-century equivalent of going viral. Every aspiring artist wanted a copy.

In these sketches, we see Hokusai at his most playful and free — a visual encyclopedist of the human condition. The Manga didn’t just document reality; it expanded it.

He also published manuals like Quick Lessons in Simplified Drawing that revealed his technique to the masses. Hokusai was an early advocate of democratized art education — the idea that anyone could learn to draw if they observed and practiced enough.

His ambition was cosmic, his humility infinite. Even his nickname, Gakyō Rōjin — “The Old Man Mad About Drawing” — sounds half self-deprecating, half divine. He wasn’t pretending to be a genius; he was simply addicted to the act of creation.

Becoming Hokusai

By the time Hokusai created The Great Wave off Kanagawa in his seventies, he had lived a dozen artistic lives. The wave wasn’t a beginning — it was a culmination, the visible crest of a lifetime’s undercurrent.

It represented everything he had learned from a century of failure, experiment, and transformation. It wasn’t the work of a prodigy; it was the reward of persistence.

And that’s what makes his story almost radical in today’s culture of instant fame. Hokusai didn’t peak in his twenties. He peaked in his seventies. He wasn’t chasing relevance; he was chasing mastery.

In an age where we worship youth and virality, Hokusai reminds us that greatness is often a slow burn — that becoming who you are might take a lifetime.

The Art of Becoming

“Hokusai before Hokusai” is not just an origin story — it’s a manifesto. A declaration that creativity is an act of self-invention, not self-discovery. The man who changed his name thirty times wasn’t indecisive; he was evolving.

In every failed sketch, every new alias, every restless move from one rented room to another, he was rehearsing immortality.

When we look at The Great Wave, we see the final form. But behind it lies a storm of lives lived, names discarded, identities tested. The true masterpiece might not be the print itself — but the man who refused to stop becoming.

Art, Religion, and the Obsession with Nature

How Hokusai Turned the Sacred into the Sublime

If The Great Wave off Kanagawa feels like a divine event — a tsunami of beauty and terror frozen in perfect balance — that’s because, in many ways, it is. It’s not just a landscape. It’s a prayer.

For Katsushika Hokusai, art and spirituality were never separate pursuits. They were two sides of the same brushstroke, two ways of trying to grasp the ungraspable. His lifelong fascination with nature wasn’t a matter of aesthetics or even philosophy — it was something deeper, closer to worship.

To draw nature was to draw the divine. To paint a wave was to paint eternity.

The Spiritual Blueprint of Nature

Japan’s native Shintō beliefs and imported Buddhist philosophy offered Hokusai a vision of the world as sacred and interconnected. In Shintō, every mountain, river, or gust of wind has a kami — a spirit. In Buddhism, nature is the mirror of impermanence, a reminder that all things flow, rise, and fall.

Hokusai’s art sits exactly where these two traditions meet.

When he painted Mount Fuji, he wasn’t simply painting a mountain. He was painting an axis — a spiritual center, a cosmic constant amid human change. His series Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji became a meditation on perception and transcendence: one mountain, infinite perspectives.

Each image in the series was a kind of visual haiku — concise, balanced, yet dense with emotion. The mountain appears calm, sleeping under a blue sky, or dwarfed by storm clouds, or refracted through waves. Through repetition, Hokusai wasn’t documenting reality; he was sanctifying it.

Fuji became his altar, and the act of depicting it, a ritual.

The Wave as a Prayer

At first glance, The Great Wave seems like a scene of chaos — nature overwhelming man. But look closer, and something else emerges.

The boats, tiny and fragile, move not against the wave but with it. The curve of the sea echoes the curve of Mount Fuji in the distance. The entire composition is a perfect circle — the Zen ensō, symbol of unity, emptiness, and enlightenment.

It’s not a painting of disaster. It’s a painting of harmony.

In Hokusai’s world, humans don’t conquer nature; they dissolve into it. The wave is not an enemy — it is the pulse of existence itself, powerful, cyclical, and divine.

He once said that with each decade he understood nature more deeply. To him, nature wasn’t an external landscape but a spiritual field of energy that art could channel. He was trying to translate something infinite into ink.

Between Earth and Heaven

In the Edo period, religion and art were deeply intertwined. Temples commissioned paintings; monks practiced calligraphy as meditation. But Hokusai’s devotion was uniquely personal.

He didn’t belong to a monastery or a school. His spirituality came from observation — the daily act of seeing. A bird in flight, a carp leaping upstream, a storm over the sea — each became a form of revelation.

His linework had the precision of calligraphy but also the spontaneity of intuition. Each brushstroke felt both controlled and liberated — like a monk’s breath during prayer.

This balance between discipline and surrender defined his genius. He wasn’t painting nature as something “out there.” He was dissolving into it, letting his body become a conduit for forces larger than himself.

And perhaps that’s what religion meant to him: not submission to doctrine, but alignment with movement — the endless rhythm of life and death, rise and fall, wave and stillness.

The Infinite Experiment

Hokusai’s obsession with nature also reflected his obsession with impermanence — the Buddhist notion that nothing stays the same.

In his sketches and prints, we see him returning to the same motifs over and over again — waves, mountains, cranes, dragons, flowers — as if trying to capture them at every stage of being. It’s not repetition; it’s devotion. Each attempt brings him closer to truth.

Late in life, he famously wrote:

“At seventy-three, I partly understand the structure of animals, birds, insects, and fish, and the life of grasses and plants. When I am eighty, I will progress further; at ninety, I shall see things more fully; and at a hundred, I will have reached the divine.”

This wasn’t arrogance. It was humility — the humility of someone who knew that mastery was infinite. For Hokusai, nature was a scripture without end, and drawing it was his form of study.

Sacred in the Ordinary

One of Hokusai’s quietest revolutions was his refusal to separate the sacred from the everyday. He found transcendence in fishermen, peasants, carpenters, and courtesans. The divine wasn’t somewhere in the heavens — it was right here, in the texture of daily life.

A wave, a gust of wind, a frog leaping into a pond — all carried spiritual weight. In his Hokusai Manga sketchbooks, divine and human figures coexist freely. Gods share pages with farmers. Demons lurk beside playful children. It’s a universe without hierarchy — an ecosystem of souls.

In this sense, Hokusai’s art feels surprisingly modern. He anticipated our ecological awareness, our yearning to reconnect with nature not as property but as kin. His vision wasn’t anthropocentric; it was holistic, ecological, cosmic.

Between Science and Spirit

What makes Hokusai so fascinating is that his spirituality was inseparable from his curiosity. He studied Western perspective and anatomy, experimented with pigments, and analyzed motion long before photography existed.

To him, the study of form was a form of faith. Science and spirit were not contradictions but companions — two ways of understanding the same mystery.

His waterfalls don’t just flow; they vibrate with rhythm. His birds don’t just fly; they trace invisible geometries of grace. He observed with the precision of a scientist but painted with the soul of a monk.

If religion sought meaning and science sought truth, Hokusai found both in the curve of a single wave.

The Old Man and the Infinite

In his final years, Hokusai lived almost like a hermit, cared for by his daughter Oi — herself a talented artist. He signed his last works as “The Old Man Mad About Drawing.”

It wasn’t madness, really. It was surrender.

He saw art as a spiritual vocation — not about recognition but transcendence. Each drawing was a step closer to the divine. He didn’t want immortality in the historical sense. He wanted union — with nature, with truth, with the great flow of things.

When he died at eighty-eight, his last recorded words were:

“If heaven will grant me another ten years — just five more — I could become a real painter.”

He was still reaching, still learning, still praying through the act of creation. That hunger — that devotion — is what makes his art feel alive even today.

Eternal Motion

In Hokusai’s universe, the line between art, religion, and nature dissolves. The sacred and the aesthetic merge into one continuous wave.

His brush captured not only what the eye could see but what the soul could sense — the rhythm of existence itself. Every ripple, every crane, every mountain was a pulse of the same infinite life.

That’s why The Great Wave still moves us. It’s not about Japan, or the sea, or even Hokusai. It’s about us — our longing for connection, our awe before forces we cannot control, our instinct to find beauty even in terror.

To look at Hokusai’s art is to stand at the edge of the eternal — and to realize that, like the wave, we too are part of it.

The Western Discovery of Hokusai: From Ukiyo-e to Impressionism

How a Japanese Master Redefined the Way the West Saw the World

When Katsushika Hokusai created The Great Wave off Kanagawa in the early 1830s, he couldn’t have imagined that, half a century later, that same wave would crash upon the shores of Europe — and change art forever.

It would take time, trade, and a series of cultural accidents, but by the late 19th century, Hokusai’s prints were everywhere: in the studios of Paris, in the hands of painters, poets, and collectors who saw in them something new, something free — a different way of seeing the world.

This was not just a cross-cultural exchange. It was a revolution.

And at its heart was a man who called himself The Old Man Mad About Drawing.

A Global Wave Born from Isolation

Ironically, Japan’s two centuries of self-imposed isolation under the Tokugawa shogunate gave rise to one of the most distinctive visual languages in the world — ukiyo-e, “pictures of the floating world.” These were images of pleasure, impermanence, and transience: theaters, courtesans, sumo wrestlers, and landscapes alive with movement and color.

When Japan finally reopened its ports to foreign trade in 1853, the West discovered these images with astonishment. To Europeans used to the heavy chiaroscuro of oil painting and the rigid hierarchy of academic art, Hokusai’s prints looked like transmissions from another planet — flat, vibrant, fearless.

They weren’t painted on canvas but printed on paper. They weren’t about kings or myths but about fishermen, mountains, rain, and light. And they carried within them a philosophy: that beauty could be ordinary, that form could breathe.

This encounter would ignite one of the most influential artistic movements in modern history — Japonisme.

Japonisme: A Shock of the Beautiful

The term “Japonisme” was coined in the 1870s to describe the European fascination with Japanese aesthetics. But “fascination” is too mild a word. It was obsession.

At flea markets and world fairs, French artists and collectors hunted down ukiyo-e prints, porcelain, and textiles. Among the treasures found in crates of imported tea were sheets of paper — wrapping material that turned out to be Hokusai prints. The discovery was electric.

Painters like Monet, Degas, Van Gogh, and Whistler began to devour these works, studying their lines, their asymmetry, their radical simplicity. The rules they had been taught — perspective, shading, proportion — suddenly seemed irrelevant. Here was a new visual logic: space as rhythm, color as emotion, line as poetry.

Hokusai became not just a name, but a catalyst. His Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji circulated like sacred texts among artists hungry for freedom.

Monet and the Infinite Reflection

Claude Monet, the apostle of light, was one of the first to absorb the Japanese lesson. His house in Giverny became a shrine to ukiyo-e — more than 200 prints adorned his walls, including several by Hokusai.

In Hokusai’s flattened compositions, Monet found permission to let go of Western perspective. The result was not imitation, but transformation. His water lilies, bridges, and rippling ponds became meditations on surface and depth — reflections of reflections.

Monet wasn’t painting nature as an object. Like Hokusai, he was painting perception itself — the way light moves, the way time flows. The garden in Giverny was his Mount Fuji.

Van Gogh: The Mad Devotee

If Monet was reverent, Vincent van Gogh was ecstatic. He once wrote to his brother Theo:

“All my work is based to some extent on Japanese art.”

He studied Hokusai obsessively, copying his prints, tracing his lines. To Van Gogh, Japanese art was pure — uncorrupted by the academic vanity of Europe. It was honest, spiritual, and alive.

He saw in Hokusai a kindred soul — another artist possessed by nature, by movement, by an uncontrollable need to create. Van Gogh painted The Bridge in the Rain (After Hiroshige) as an homage, and even created a portrait of a Japanese artist surrounded by cherry blossoms, an imagined self-portrait of transcendence.

But it was Hokusai’s Great Wave that haunted him most. He saw in it the same force that he felt in himself: beauty teetering on the edge of chaos, a divine restlessness. “The waves,” he wrote, “are claws reaching for the sky.” He might as well have been describing his own mind.

Degas, Whistler, and the Geometry of Grace

While Van Gogh and Monet absorbed Hokusai’s emotion, others like Edgar Degas and James McNeill Whistler drew from his structure. They were fascinated by his ability to turn space into design — the way a single curve could define an entire composition.

Degas, in particular, borrowed Hokusai’s cropped perspectives, tilting viewpoints, and off-center compositions to capture dancers mid-motion. His ballet scenes, with their floating figures and oblique angles, owe as much to Japanese woodblock prints as to classical art.

Whistler, too, infused his paintings with Hokusai’s rhythm. His famous Nocturne in Blue and Gold could almost be read as a Western ukiyo-e: minimal, musical, suspended between form and feeling.

Beyond Technique: A New Philosophy of Seeing

What Western artists learned from Hokusai wasn’t just a set of visual tricks. It was a new philosophy — a way to see the world not as hierarchy, but as harmony.

In ukiyo-e, there was no central subject, no vanishing point commanding the viewer’s gaze. Every element — a cloud, a wave, a fisherman’s oar — carried equal weight. It was democracy on paper, long before the term had meaning in art.

Hokusai’s sense of flow and balance would echo in movements from Art Nouveau to Cubism. His belief that beauty could exist in the mundane laid the foundation for modern design, photography, and even animation. Studio Ghibli’s Hayao Miyazaki has called Hokusai a “spiritual ancestor.”

Through his brush, the East and the West met — not in opposition, but in resonance.

A Bridge Between Worlds

The irony of Hokusai’s fame is that he never set out to be a global icon. He lived and died within the boundaries of Edo Japan, barely imagining the scale of his eventual impact.

Yet, through the serendipity of trade and curiosity, his vision leapt continents. His wave crossed oceans, reshaped minds, and entered collective imagination — an early act of cultural globalization through beauty rather than conquest.

When Western artists painted with Hokusai in their hearts, they weren’t just borrowing technique. They were joining a centuries-old conversation about nature, impermanence, and the fragile poetry of existence.

The Eternal Return

Today, Hokusai’s influence feels almost invisible because it is everywhere — in design, in cinema, in visual culture itself. Every minimalist poster, every stylized wave, every use of negative space carries a trace of his line.

More than any single artwork, Hokusai gave us a way to see — to find infinity in the ordinary, to embrace the flow between worlds.

The West discovered Hokusai, but perhaps the deeper truth is that Hokusai discovered the West long before it discovered him. His curiosity, his hunger for perspective, his willingness to experiment were already global in spirit.

Art, for him, was never confined by borders. It was a universal language of form and feeling — a bridge built from ink, paper, and vision.

The Wave Still Travels

Nearly two centuries later, The Great Wave continues to move — across oceans, across generations, across screens. It adorns tattoos, album covers, emojis, and fine art museums alike.

But beneath its ubiquity, the wave still whispers its original message: everything flows, everything connects.

When Hokusai painted it, he was an old man seeking eternity. What he found was something even greater — universality.

In the undulating line of his wave, he drew not just Japan or nature or art, but the endless conversation between worlds.

And that, perhaps, is the truest definition of masterpiece.

The Eternal Student

Even as he aged, Hokusai saw himself not as a master, but as a student. That humility — that refusal to claim completion — was his greatest genius.

In Japan, mastery is often associated with repetition and discipline. But Hokusai practiced a different kind of mastery — one rooted in curiosity, impermanence, and experimentation. He believed art was a living organism, one that must keep changing to survive.

It’s this attitude that makes him a precursor not just to modern art, but to modern thought. He approached the world not as a fixed system to be represented, but as a flux to be experienced.

In many ways, he was the first truly modern artist: restless, self-aware, forever reinventing himself.

Death as Continuation

When he died in 1849, Hokusai’s final words reportedly were:

“If Heaven will give me just another ten years… Just another five years… then I could become a real painter.”

It’s hard to imagine a more perfect epitaph. He didn’t ask for fame, wealth, or peace — only time.

That longing for one more day, one more stroke, one more vision — it’s the heartbeat of every artist. In that sense, Hokusai never really died. His work continued to ripple outward, touching lives far beyond his own.

The “wave” that conquered the world was not just a picture. It was a metaphor for this endless continuation — the persistence of art beyond mortality. The crest falls, the foam dissolves, but the sea remains.

The Legacy That Shaped the Future

After his death, Hokusai’s art traveled further and faster than any boat he could have imagined. The West embraced him as a prophet of modernity. Impressionists, Symbolists, and later Expressionists saw in his simplicity a radical purity — a rejection of illusion in favor of emotion.

His compositions anticipated photography. His line predicted graphic design. His sense of movement foreshadowed cinema. The Great Wave itself has become so universal that it no longer belongs to any one culture. It is a planetary image — as familiar as the Mona Lisa or Van Gogh’s Starry Night.

And yet, for all its fame, Hokusai’s wave retains its mystery. It resists consumption. It stares back at us, daring us to see what he saw: the beauty of impermanence, the divine in the everyday.

The Philosophy of a Mad Genius

What set Hokusai apart from his peers was not only his technical mastery but his philosophy — a worldview shaped by Shinto, Buddhism, and Taoism.

He believed in the cyclical nature of life: everything flows, everything transforms. Mountains erode into rivers; waves rise and fall; death feeds birth. His art didn’t depict permanence but motion — the cosmic dance between being and becoming.

For Hokusai, the divine was not in temples or scriptures, but in the act of creation itself. Drawing was a prayer. Each brushstroke was a moment of meditation, a fragment of the infinite.

This spiritual perspective infused even his most secular images with transcendence. His fishermen, trees, and birds seem to vibrate with an unseen energy — as if nature itself were breathing through his hand.

From Edo to Eternity

Two centuries later, Hokusai’s influence has seeped into nearly every corner of culture. His aesthetics shaped Japanese manga and anime, inspired fashion houses and architects, and even guided digital artists designing pixels instead of prints.

Every time we admire minimalism, flow, or harmony between nature and technology, we are, in some way, echoing Hokusai’s vision.

And yet, beyond all this cultural magnitude, there remains something deeply human about him — the image of an old man sitting on the floor of a small room, surrounded by paper, still chasing perfection, still believing that the next line might finally be it.

The Endless Wave

Hokusai’s story reminds us that greatness is not about arrival, but about pursuit. To be “mad about drawing” is to understand that art — and life — is never finished.

Every artist who strives for something unreachable, every creator who stays up one more hour chasing the right note, color, or word, is continuing Hokusai’s work.

His wave still moves, not across oceans, but through generations — through each of us who create, destroy, and begin again.

He once said, “From the age of six, I had a mania for drawing the form of things.” That mania became immortality.

Hokusai didn’t conquer the world. He dissolved into it — and in doing so, became eternal.