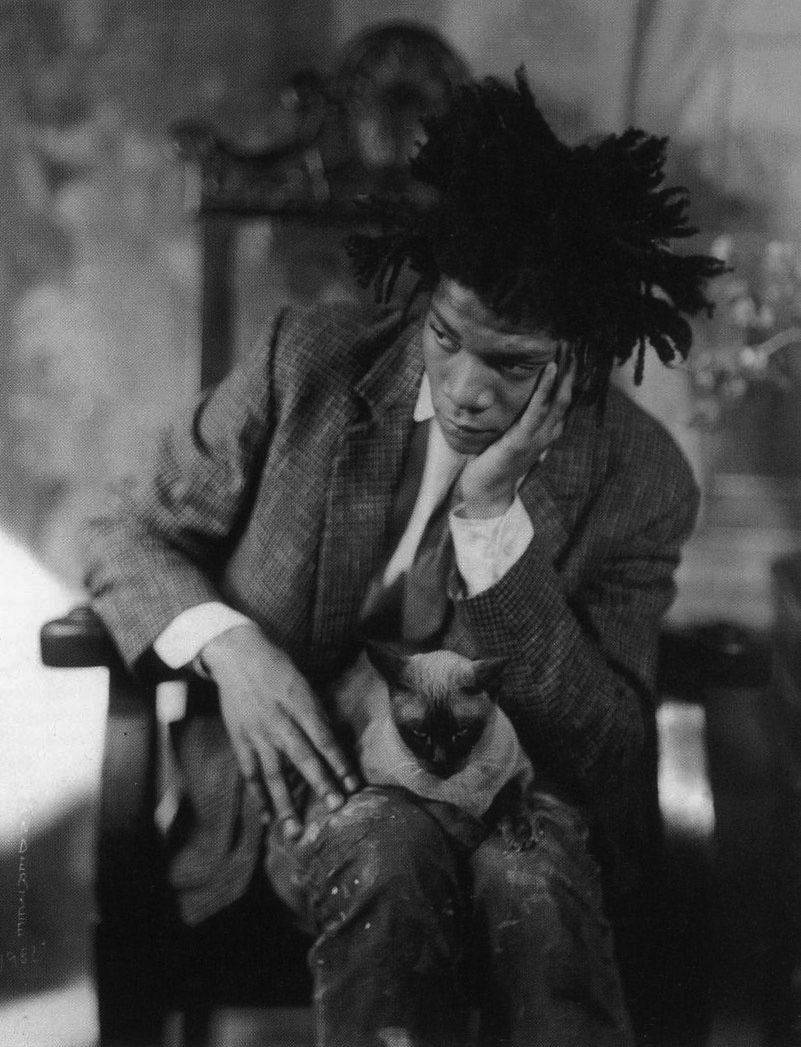

Before Jean-Michel Basquiat became a market category, a museum staple, and a record-breaking auction name, he was a disruption mechanism with a spray can and a reading habit. The myth likes him raw, chaotic, and meteoric. The reality is more interesting: Basquiat was intellectually armed and visually strategic long before the art world decided he was profitable.

He did not “arrive.” He infiltrated.

SAMO Was Not a Phase — It Was a Thesis

Basquiat’s early graffiti signature — SAMO — was not tagging in the conventional sense. It was conceptual street poetry. Short phrases, cryptic social commentary, anti-commodity slogans. It functioned more like public philosophy than vandalism.

This matters because it reframes his trajectory. Basquiat did not evolve from street to gallery. He was always operating conceptually — the surface just changed.

Street walls were simply his first publishing platform.

The Vocabulary Advantage

Unlike the stereotype of the instinctive street prodigy, Basquiat was intensely literate. Anatomy books, history, jazz, poetry, race theory — these weren’t later influences. They were early fuel. His canvases look spontaneous but read encyclopedic.

Words appear not as decoration but as anchors. Names, fragments, lists, crossed-out terms — language becomes texture. This hybrid of text and image would later define his signature visual rhythm.

Major institutions like the Guggenheim’s Basquiat collection notes emphasize how deliberately he fused semiotics with painterly aggression — not as rebellion alone, but as method.

Why the Market Didn’t Understand Him — Then Overstood Him

Early collectors saw raw energy. Later collectors saw investment. Both missed the structural critique embedded in the work itself: Basquiat painted power, race, money, and historical erasure while being absorbed by the very systems he dissected.

That tension is not irony — it’s the core of his legacy.

Luxury didn’t adopt Basquiat because he became safe. Luxury adopted him because he became unavoidable.

The Crown Motif Was Not Ego

The famous three-point crown is often misread as self-coronation. In reality, it frequently marks Black figures erased by official history — athletes, musicians, cultural heroes. It is annotation, not vanity.

Basquiat painted correction into the record.

That corrective instinct — rewriting hierarchy through symbol — is something contemporary satirical artists also deploy, though often with colder irony, as seen in Art-Sheep’s coverage of modern symbolic critique in illustration.

The Disruption That Stuck

Many disruptive artists are later neutralized by museums. Basquiat resists full neutralization because the discomfort remains legible. The work still vibrates with accusation.

He didn’t just enter the art world.

He changed what it had to pretend to see.