The internet promised us a beautiful lie: that culture would become borderless. That once museums digitized their collections, once archives went high-resolution, once exhibitions became virtual walkthroughs, art would finally escape geography. The Louvre in your pocket. The British Museum on your couch. The world — scrollable.

Reality, as always, arrived with footnotes, licensing agreements, and regional restrictions.

Yes, museums are online. No, they are not equally online for everyone.

And that gap is becoming one of the strangest cultural divides of the digital age.

The Great Digitization Dream

Over the last decade, museums and cultural institutions have raced to digitize everything: paintings, manuscripts, sculptures, film archives, audio collections, exhibition catalogs, conservation scans. The motivation was noble and practical at once — preservation, accessibility, education, and, not incidentally, relevance.

When physical doors close — pandemics, wars, funding crises — digital doors keep the institution alive.

Major institutions now host massive online collections and virtual tours, such as those aggregated through platforms like Google Arts & Culture, where users can browse artworks, zoom into brushstrokes, and explore curated digital exhibitions from hundreds of partners worldwide.

It looks like universal access.

It isn’t.

The Hidden Borders of Digital Culture

Digital does not mean unrestricted. It simply means restricted differently.

Many museum videos, archive films, recorded lectures, and special exhibitions are governed by:

-

regional licensing contracts

-

distribution agreements

-

donor restrictions

-

copyright zones

-

platform-level geo-blocking

So the same exhibition stream that works in Berlin fails in Toronto. The same archive video visible in London is unavailable in Sydney. The same digitized material loads in New York and disappears in parts of Asia.

The user experience message is always polite and infuriatingly vague:

“This content is not available in your region.”

Nothing says “global culture” like a digital velvet rope.

When Access Depends on Infrastructure

We like to imagine cultural access as a moral question — open vs closed, public vs private. Increasingly, it is a technical one. Access depends on infrastructure layers most users never see: routing, permissions, hosting contracts, distribution filters.

This has produced a quiet behavioral shift. Researchers, students, and independent creators have begun treating access tools as part of their normal cultural toolkit. Not to “hack” culture, but to reach what is already meant to be public but is unevenly distributed.

That is where privacy and routing tools — including services like VeePN VPN apps — enter the picture for many users trying to reach region-restricted archives, museum platforms, and digital exhibitions that are technically online but practically fenced.

Not rebellion. Workaround.

The Irony of the Digital Museum

Physical museums exclude by distance and cost. Digital museums exclude by policy and protocol. We solved the airplane problem and replaced it with a permissions problem.

The irony is sharp: a public museum funded partly by taxpayers can end up digitally unavailable to large segments of the global public — not by intent, but by contract layering. Culture becomes globally visible but selectively reachable.

It creates a new class divide:

-

those who know how to navigate digital barriers

-

and those who assume the barrier means “does not exist”

From a cultural standpoint, that’s dangerous. Visibility without accessibility produces distorted narratives about what survives and what matters.

Art History, Filtered by Region

Imagine learning art history where half the slides randomly fail to load depending on your country. That is increasingly the student experience with digital archives, recorded symposia, and exhibition media.

Scholars adapt. They share mirrors, alternative hosts, institutional logins, routing methods. Informal access networks emerge — academic folklore for the bandwidth age.

This is not piracy culture. It is access culture trying to keep up with licensing culture.

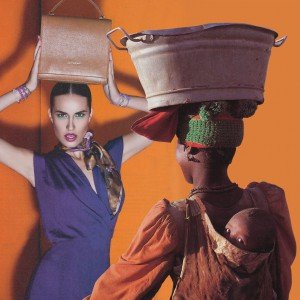

Contemporary artists have already begun critiquing this layered visibility — the idea that what you can see defines what you believe exists. Visual satirists and symbolic illustrators frequently frame modern systems as selectively transparent — a theme explored sharply in works like those featured in this Art-Sheep spotlight on Pawel Kuczynski, where access, control, and perception are inseparable.

The Rise of the Proxy Visitor

We are entering the era of the proxy visitor — the person who visits culture through layered mediation:

platform → license → region → routing → device → interface.

The museum visit used to require travel. Now it requires configuration.

This doesn’t make digital museums a failure — far from it. Digitization remains one of the greatest preservation achievements in cultural history. Fires, floods, and wars erase originals. High-resolution scans survive them.

But it does mean we should retire the naïve slogan that “putting it online makes it universal.”

Online is not universal.

Online is conditional.

What Institutions Will Need to Decide

Cultural institutions now face a strategic question: are they building digital showcases or digital commons?

A showcase tolerates restricted viewing.

A commons fights for maximum accessibility.

The answer will shape how the next generation understands art history — as shared inheritance or licensed experience.

The New Cultural Literacy

In the meantime, cultural literacy is acquiring a technical layer. Knowing where art lives is no longer enough. You must also know how it is delivered, filtered, and sometimes blocked.

The modern museum visitor needs curiosity, taste — and occasionally network awareness.

Not quite what the Renaissance had in mind.

But then again, neither were streaming servers.

If culture is going to live online, it will also have to learn how to travel.