In every age, stories have heroes — shining figures who embody courage, clarity, and virtue. But the twentieth century introduced something more ambivalent, messier, and deeply modern: the anti-hero. This isn’t the caped knight or the noble protagonist. Instead, it is the conflicted, contradictory, and often morally dubious figure who refuses easy categorization yet somehow reflects the world back at us with greater fidelity than a classic hero ever could. Today’s cultural landscape, saturated with figures like Walter White, Rick Sanchez, and even Travis Bickle, owes much of its DNA to this lineage.

The term itself — “antihero” — describes a character who stands in opposition to the classical heroic ideal. Anti-heroes are often flawed, introspective, and driven by motives that defy the noble quests of their predecessors; they act not because the world needs saving, but because they are compelled to act at all — even if that action teeters on chaos. According to literary theory, the anti-hero emerged in the eighteenth century and evolved into a staple of modern fiction precisely because it confronted society’s increasing complexity and moral ambiguity.

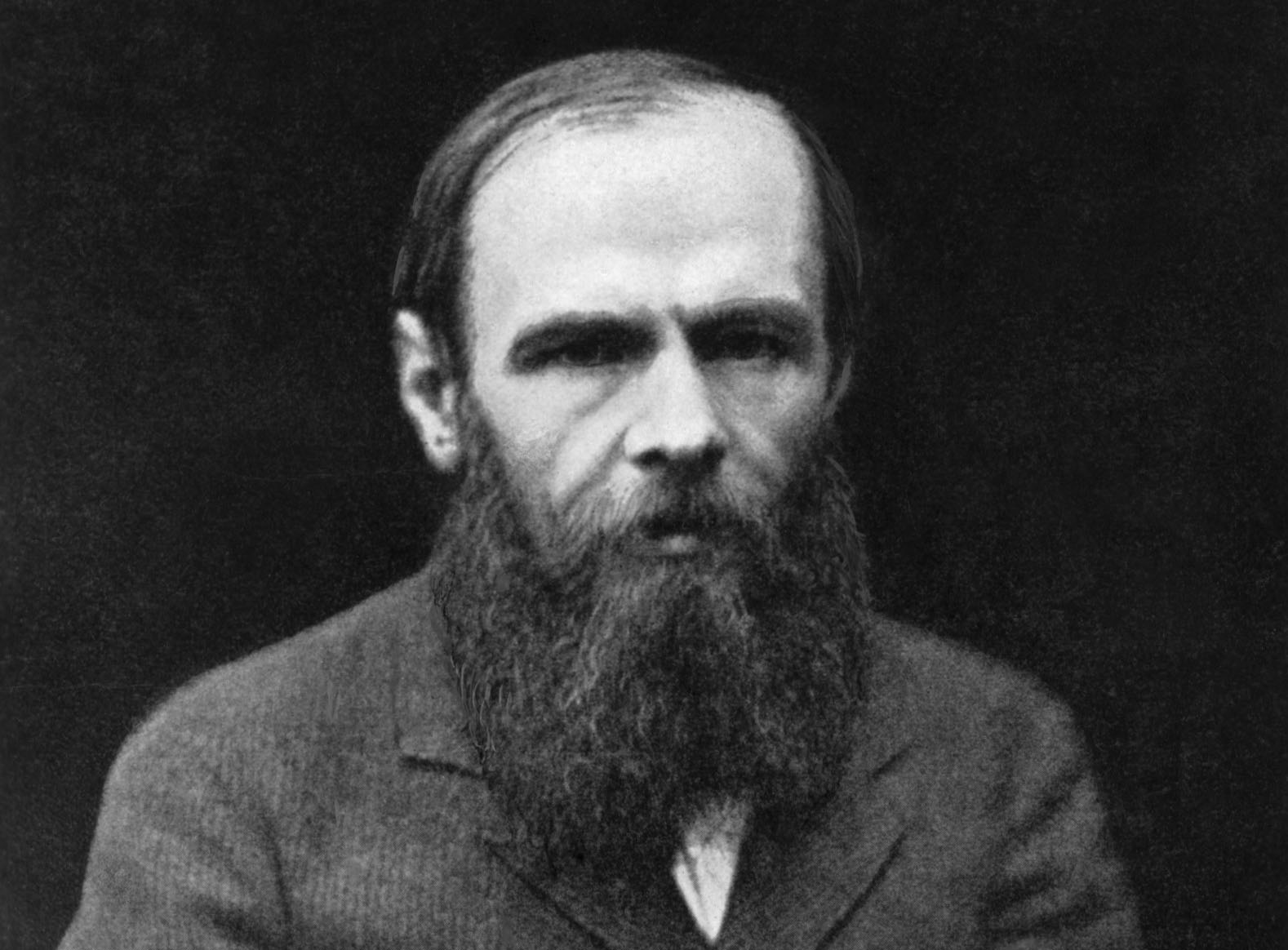

A key ancestor of the modern anti-hero is found in Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underground (1864). The unnamed narrator — often referred to as the “Underground Man” — represents a radical departure from conventional protagonists. He is introspective, resentful, self-sabotaging and profoundly isolated, all while offering a blistering critique of rationalism, complacency, and the social norms of his time. That disaffected voice — wry, self-aware, and at odds with the world — set a template for characters to come.

Almost a century later, cinema captured this spirit through a different medium. Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver (1976) introduced audiences to Travis Bickle, a Vietnam veteran whose loneliness, alienation, and simmering disillusionment made him one of film history’s most unnerving anti-heroes. While Bickle’s world is gritty and urban rather than existential and philosophical, his psychological landscape echoes that of Dostoevsky’s Underground Man: both are outsiders in a society they feel alienated from, both are consumed with confronting realities they neither understand nor can reconcile with. GradeSaver

This shift from heroic idealism to anti-heroic introspection reflects larger cultural movements. In the nineteenth century, industrialization and urbanization splintered communal life and introduced conditions of anonymity and fragmentation. By the twentieth century, two World Wars, economic depression, and the pressures of modernity had rendered the old heroic archetype inadequate. The anti-hero wasn’t just a literary or cinematic figure — it was a response to modern consciousness itself.

Over the decades, this archetype has mutated and proliferated. Mid-century existentialists like Albert Camus and Jean-Paul Sartre explored figures who act even when life appears devoid of intrinsic meaning. In parallel, Dostoevsky’s protagonists had already begun probing similar territory — humans driven by paradox, doubt, and inner conflict. The anti-hero does not defeat evil. He lives with it, negotiates it, and often embodies it. And in doing so, he reveals as much about society as he does about himself.

In contemporary pop culture, from television dramas to graphic novels, anti-heroes dominate our screens and our imaginations. Figures like Tony Soprano and Walter White do not earn our admiration in the traditional sense, but we feel for them. They are not idealized. They are recognizable. They are mirrors to our own moral complexities.

If you want to explore how modern creators reinterpret archetypes and narrative expectations, check out our feature on Pawel Kuczynski’s satirical societal critiques

— where visual art picks up the thread of cultural contradiction where literature and cinema leave off.

In the end, the anti-hero is not just a character type. It is a cultural confession: that we, as readers and viewers, seek stories that reflect our uncertainty, our flaws, our unease with simple moral binaries. The birth of the anti-hero marked not just a shift in narrative form, but a reorientation of empathy, one that continues to shape how we tell stories about ourselves and the world we inhabit.