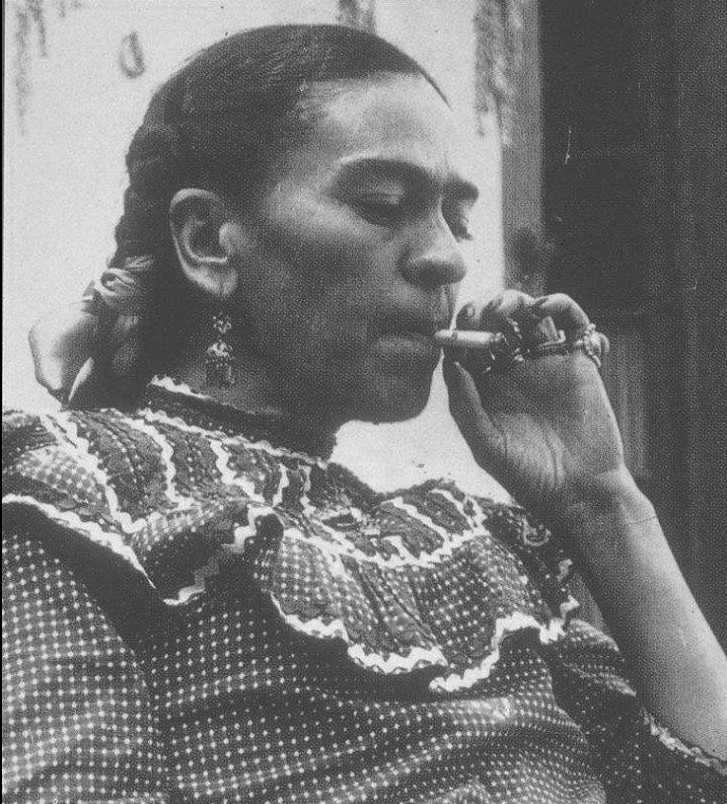

Mexican Surrealist painter Frida Kahlo was born in Mexico City in 1907, and spent the majority of her life here. Often forced to stay within the confines of her bed due to physical limitations, the artist painted self-portraits, and using her vast imagination and incredible strength she helped to unite the public through the portrayal of her own personal anguish onto the canvas. The story of her life is told in Mexico City, within the walls of her family home, La Casa Azul.

Frida Kahlo was a righteous, vivid and brilliant painter whose eventful life is today documented and celebrated in her old family home, which was converted into a museum by her late husband, Diego Rivera. Throughout her life, she was surrounded by influential social and political figures; her husband for example was one of the important muralists of the time, and the two of them were active in the Communist party. From a young age, Kahlo presented herself as strong-minded, disagreeing frequently with peers at her school, in which she was one of only 30 female students. A revolutionary, she was known for her good-humoured, tequila-drinking, warm and welcoming nature. She first met her husband, Diego Rivera, in the mid 1920s, when they became friends and colleagues. They later married in 1929. Their marriage was long and loving, and following their separation and the creation of Kahlo’s largest painting, The Two Fridas (1939), they remarried at the end of 1940.

‘The Blue House’ is located in Mexico City, in the suburb of Covoacán. This suburb, especially the area of Colonia del Carmen, was a thriving intellects hangout, full of important innovative figures during the 1920s and after. Leon Trotsky, a Russian Marxist revolutionary, was a friend of both Rivera and Kahlo, and took refuge in the house during 1937 to 1939 whilst he was under threat from Stalin. During his stay many other Communist intellectuals would come to the house, which lead to Kahlo’s works being introduced to several important figures such as founder of Surrealism André Breton. It was he, Kahlo said, who first made her aware that her paintings were of a Surrealist style. Everyone who met Frida Kahlo claimed to be uplifted by her passion and lust for life. Trotsky in particular was very taken with Kahlo, and they had a brief romantic relationship. After a first failed attempt on his life by muralist David Siqueiros, Trotsky was tragically murdered in 1940.

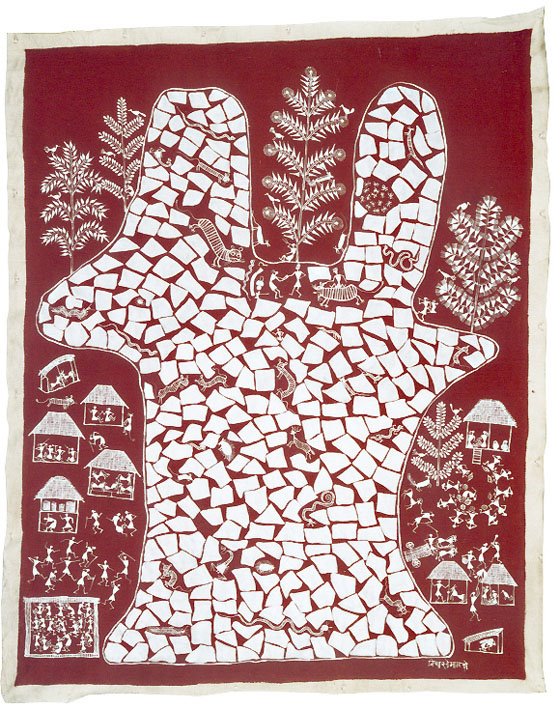

Frida Kahlo was born in La Casa Azul and died here, in one of the upstairs corner rooms. The works of art and items on display at the museum give an intimate look into Frida Kahlo’s life, her tumultuous marriage with her husband, her family and the ongoing problems she went through with her own body. The museum contains some of her painted works, but also works from other artists from the time, many of which are from Kahlo’s personal collection. Presenting Frida Kahlo as a person, and as a much loved and revered artist, the house is maintained in a similar fashion to how it was kept in the 1950s. In addition to her personal works it contains folk art, personal items, photographs, memorabilia and other interesting artefacts and items such as the small portrait of Rivera that Kahlo used to carry around with her. Items such as these give a very personal view into her life and the environment in which she lived.

The building’s architecture is interesting as it was originally created in 1904 in a French style, but was adapted later by Rivera and Kahlo in 1941 – following the death of Kahlo’s father – to have a bigger garden and brighter colours such as the blue painted walls which can be seen today. The house was donated and opened as a museum in 1958 by Diego Rivera, and consists of ten rooms over two floors. No photographs are allowed to be taken within the actual building itself, but are permitted outside, for example in the stunning patio and courtyard, which also shows evidence of Kahlo’s life. Decorated with wild and colourful flowers, Mexican art and ‘Judases’ line the brightly painted courtyard.

Mexico in the early 20th century was a very important place politically, following the revolution and the fall of the dictatorship in 1910, the country was hurled into social upheaval, struggle and warfare for the next seven years. Art at the time was a very political act, and like her husband Rivera and social artists David Siqueiros and José Clemente Orozco, many of the main artists were muralists. Wall paintings was made with the belief that art was for the people, the people’s property. Frida Kahlo was influenced by travel; in 1931 she went with Rivera to New York for his exhibition at the (then) new museum, the Museum of Modern Art. It was during this time in America when Rivera painted the famous Rockefeller lobby, which pictured Nelson Rockefeller next to a portrait of Vladmir Lenin, a Russian Communist and revolutionary. Refusing to change the work after being forced to, it was ripped down.

Kahlo was also influenced by current happenings in the news, often choosing stories that portrayed the pain she felt from her own personal experiences. For exampleA Few Little Nips (1935) is thought to be a portrayal of a famous news headline of the time about a husband who had stabbed his wife 22 times and reflects Kahlo’s pain of discovering her husband and sister’s sexual relationship. Brutally vivid works such as this are representative of Kahlo’s expressive style, and her imagination captured the gazes of many, leading her to be one of the most individual artists of her time. Although not fitting in with the Mexican Muralism art ‘of the people’, Kahlo’s works on canvas spoke to people in a way that other typical political pieces did not. It carried the message that most people can cope with more pain than they initially think, and that there is a common perception by people that they are alone in suffering.

Frida Kahlo’s life was tragic and full of agonies, both physical and mental. She survived polio at the age of six, and at just 18 she was in a terrible accident that severely damaged her body to such an extent that most doctors thought she would never walk again. During the extensive amount of time she spent bedridden, she would draw and later began to paint, following the purchase of an easel and paints provided by her parents. Permanently in and out of hospital due to having bones reset and further operations intended to help her body heal, she felt physical pain her entire life, and her works were often reflective of this. Broken Column(1943) shows the artist bare breasted, wearing her metal brace, with her face and body covered in pins.

The accident caused her to have problems having children, and although she fell pregnant three times, she never managed to successfully conceive. The distress this brought is portrayed in several of her paintings, one of the most shocking of which is Henry Ford Hospital (1932). Created following her second miscarriage, this painting illustrates her knowledge of medicine, which she had studied prior to her accident. In 1953 she had her first art exhibition in her home country of Mexico, and this would be the only exhibition in her lifetime, as she passed away at the age of 47 in 1954.

Today, the Frida Kahlo Museum is one of the most visited museums in Mexico City, as thousands flock there every year to take a look into the extraordinary life of one of the most celebrated female artists of all time. Wherever she went, her presence was felt, and even in death during her cremation ceremony, observers claimed to see her smile slightly as her last wish to have her body burned was granted. The final entry into her diary read:

‘I hope the end is joyful – and I hope never to return – Frida’.